What Do You Actually Want & How Bad Do You Want It?

How gratitude, contentment & desire work synergistically (not in opposition!) to fuel creativity. Plus, an AI writing exercise (yes, AI! we'll discuss!) to take your writing into brand-new territory.

I have spent the last several years—I guess it started more than a decade ago, with Danielle Laporte’s book, Desire Map—on a self-guided study of desire.

In Desire Map, I learned for the first time to really question what I believed I wanted by asking myself not what I wanted but rather how I wanted to feel in association with the thing I wanted. In other words, if I told myself I wanted to write and publish a book, Desire Map would challenge me to dig a little deeper and ask myself what it was I wanted to feel in association with writing and publishing a book. I think Laporte called the feelings we’re after “core desired feelings” or something like that.

I don’t remember all the details, and, to be honest, it’s not exactly the kind of book I typically gravitate to, but this concept of core desired feelings was life-changing for me. It helped me to realize that of course we we are motivated by how we want to feel! And if we fail to recognize that, we might chase the wrong things, things we tell ourselves we want, but that won’t deliver those core desired feelings we’re actually after, especially if we haven’t taken the time to know what those feelings are.

That was all the way back around 2010 or 2011 when I was reading Desire Map.

From there, I began to really focus on my core desired feelings, and interrogate my “goals” more actively to make sure they were aligned with the feelings I wanted. And you know what? Sometimes they weren’t aligned! And I was able to see it. And let that goal go, or revise it.

Even still, I can sometimes find myself thinking I want a thing … and then realizing, with a little more inspection, that I don’t. Maybe I’m just programmed to want it because it lies somewhere “ahead” of me on my career or life path (Note to self: Life is not a straight line! There is no ahead, and no behind). Or maybe I discover I’m just jealous of a really cool person who has a certain thing or has done a certain thing. But I might not recognize those minor delusions without looking closely at the thing itself in comparison to my core desired feelings.

Getting more in touch with my core desired feelings eventually opened the door to a much deeper dive into the art and science of wanting as a state in and of itself: the ache of it, yes, but also the heat of it, and perhaps most especially the stigma around desire in our culture, especially for women. I am most urgently interested in the role desire plays in our creative lives. Ultimately, I’ve become convinced that desire does—and must—drive our creative pursuits.

Desire is both fuel and engine for our art.

At its core, desire is a state of wanting and wanting is inherently vulnerable. Vulnerability, in turn, is essential for creativity, because creativity by its very nature implies risk and pain. Why? Because creativity can and often does lead to failure of all kinds. Failure of our art to live up to our vision. Failure to make our art in the first place. Failure of the art to please anyone or garner any attention. Failure to try again after failing. If we’re sincere, which to my mind means we’re doing it right, our art can (and sometimes will) break our hearts. And part of doing it “right”—in my experience—involves allowing ourselves to want unabashedly. Allowing ourselves to hunger without apology.

When we wrap ourselves in the seemingly protective armor of not wanting (oh, this old project is nothing, really, I’m sure it will never come to anything, but that’s okay, I don’t care about it all that much), we dilute the alchemical force of the natural desire that can keep us working even when the work is hard indeed, even when the work is painful, even when the work isn’t working and we worry it never will.

In those difficult creative moments (or stretches—sometimes these feelings last years!), it’s the strength of our desire that directs us forward, keeps us moving in spite of the odds against us. On this topic, Octavia Butler wrote some of the most prescient, potent words I’ve ever read:

All prayers are to Self

And, in one way or another,

All prayers are answered.

Pray,

But beware.

Your desires,

Whether or not you achieve them

Will determine who you become.

Some of you have heard me talk about this before, so this recap will be brief: I was first introduced to Butler’s writings on desire by Maria Papova, in her brilliant newsletter The Marginalian. Papova writes:

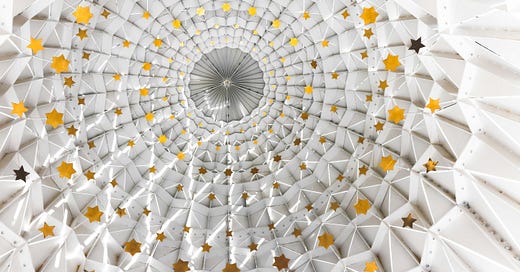

“Butler’s sentiment is only magnified by knowing that the word desire derives from the Latin for ‘without a star,’ radiating a longing for direction. It is by wanting that we orient ourselves in the world, by finding and following our private North Star that we walk the path of becoming.”

That is so breathtakingly beautiful a concept—this idea of desire as a longing for direction stemming from starlessness, the state of being “without a star.” It’s just so achingly lovely.

And yet.

I’ve also been thinking a great deal about the elusive art of contentment, and its role in our lives and our creative practices. A writer friend of mine said recently—on the occasion of a significant health anniversary—that there is “nothing she could have wanted for in this life that she hasn’t had in abundance.” She said that at age 54, which, coincidentally, is the age I am now, she gets to be “a woman whose dearest dreams have all come true.”

My friend’s words awed me, truly.

It was almost as if her sentences shone from within. Was that the glow of contentment shining through, I wondered? Does contentment make its own light? I couldn’t help but ask myself whether I could honestly say what my friend said.

Have I had everything I could have wanted in this life, and in abundance?

Have my dearest dreams all come true?

Hmm.

On both counts, I might say, close, but not quite. That is, I’ve experienced many hoped-for things, but not all. There’s one longing in particular that I dearly hope to fulfill before my time is up, a longing related to a fracture in our family, a broken limb in the tree that is the whole of us.

Healing that fracture is not entirely or even largely within my control, but, then, what is entirely within our control when it comes to wish fulfillment? I can only edge my way toward the object of my desire, feeling in the dark for solutions, humming prayers as I go.

As for dreams, it’s true that many of mine have come true in this lifetime—including some I could never have believed would manifest, and some I didn’t even know were dreams until they landed in my lap. But some important dreams remain largely outstanding, including the dream of finishing my novel. While my debut memoir, The Part That Burns, was an essential book for me to write, my childhood dreams around writing involved something more like playacting, where you’re making it all up as you go along, building a world with its own order and rules, its own places and characters and problems, its own dreamscapes of possibility. In other words, a novel. That’s what I always, from the time I was a child, imagined myself doing when I “grew up” to be a writer. I am now closer than I have ever been, and believe more wholly in myself and the project than ever before.

This leaves me with the conundrum of how to balance the poles of desire and contentment. I want—and even need—to want in order to create. But I also want—and even need—to be content and grateful for what I already have.

What I’ve come to realize is this: we can be content even while wanting, as long as we believe wholly in the inevitability of want’s fulfillment.

That is to say, we must assume what we work toward will come to pass. That’s because contentment, I am realizing, comes not only from practicing gratitude for what we already have, but also from practicing gratitude in advance for everything we still want as well as for the wanting itself.

In other words, I need to feel grateful already for the fact that I will finish my novel, as well as grateful for my persistent desire to do so. Through this bidirectional practice of gratitude, we can stoke the fire of our desires without burning ourselves, whether on the leaping flames of comparative ambition—and we all know how awful that feels—or on the bitter embers that smolder wherever our desires are kept secret and airless.

As Octavia Butler writes, “If you want a thing — truly want it, want it so badly that you need it as you need air to breathe, then unless you die, you will have it. Why not? It has you. There is no escape. What a cruel and terrible thing escape would be if escape were possible.”

If desire is a fuel for creative practice, attention is the tank for that fuel. Attention is where inspiration comes from, and is essential for an ongoing practice of collecting and cataloguing the bits and pieces of things that will later become our stories, essays, poems, poem-ish things, and books.

The idea being, we have to pay attention to the world, really close attention, and keep track of what catches our eye—the shimmers and shards of life. Write them down. Record it, but don’t make anything of it. No story, no explanation. Just the thing itself. Later, you get to return to it and say, “what is this thing, and why did it catch my attention?” You can start riffing on it, testing it, pushing it and pulling it to see what it’s made of. At the end of the day, almost everything comes down to the quality of our attention. The older I get, the more I know this is simply the first and most important truth of good writing. As Simone Weil put it:

“Attention, taken to its highest degree, is the same thing as prayer….If we turn our mind toward the good, it is impossible that little by little the whole soul will not be attracted thereto in spite of itself.”

This week’s writing prompt is inspired by Vauhini Vara’s incredible essay in Best American Essays 2022. And it is a truly incredible essay.

So let’s look together at what Vauhini Vara did in her essay, including her process notes on how she used AI (so generous!), then we’ll play around with some strategies of our own to see if we can find our way into something really new.