Before we jump in, an apology for not sending a Monday post. Jon and I were in Portland this past weekend visiting our granddaughter, Cora, and Jon ended up in the ER with a respiratory problem, like a severe asthma attack, although he’s never had asthma. What he has had is a chronic [something something with sinus and coughing and tightness and, and] that started last summer and has come and gone ever since. He’s okay now, though the underlying issue is not solved. Next week, he goes to Mayo for a full work-up, which we hope will lead to better answers.

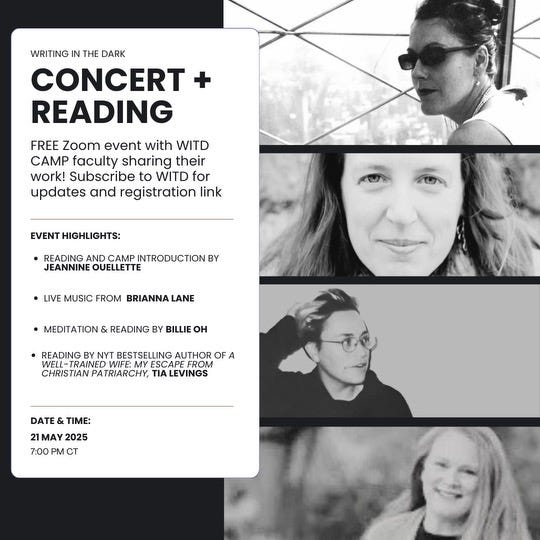

Also: we’re having a WITD party—a Concert + Reading—and we hope you’ll come. It will be an evening full of light and love and celebration, readings, music, and conversation about creative community and our vision for this summer’s WITD | The CAMP. It’s free—all you need to do is register here to receive the Zoom link which will be sent day of.

And now for pleasure.

It has been—it is—so fascinating to explore this concept with you all. Pleasure, it turns out, and not surprisingly, is complex. It’s not the same as joy, nor is it always comfort. Pleasure is richer, stranger—a subtle heat, a velvet hum beneath the noise of necessity.

Virginia Woolf once wrote:

Pleasure has no logic; it never asks permission. It just comes.

That might be the true, strange genius of pleasure. How it arrives where the rational falters. I remember this phenomenon so vividly from the years of my traumatic divorce—the way pleasure could envelop me in spite of, and, at times, it seemed, even because of the abject pain that swallowed me. Years ago, from inside of that drama, I wrote about how it felt, and I re-shared that essay here in the post, Later This Girl Will Drive With Windows Down And Sing. But First She Will Tremble on The Cliff Above Her Terrible Divorce (I’ve removed the archival paywall in case you want to read or re-read it).

What I found back then, and still find now, is that pleasure—sometimes of its own accord, and sometimes in defiance of what’s rational—slips in through the senses and blooms into fullness, sometimes slowly, sometimes in a burst: the first sip of something bitter and hot on a cold morning, the hush after laughter, when silence hovers warmly between us, the first tender green leaves of spring. The beauty of pleasure lies not in its grandeur but in its detail, in its texture—the way it folds into the ordinary and transforms it.

Pleasure is textural because it touches so many thresholds at once: body, mind, memory. It is not merely experienced but felt—with a fullness that often resists language. Vladimir Nabokov captured this with rare clarity when he described the “tingle of the spine” as his test for art’s greatness. That same tingle is the essence of pleasure, not in what it gives us, but in how it stirs us.

Think of the slow slide of sunlight across a wooden floor, the ache behind the ribs when a piece of music finds the hidden key to your inner life. Each carries its own grain, its own rhythm. Pleasure is sensual, yes, but also cerebral, emotional, temporal. It gathers the past like honey holds the memory of the flower.

And pleasure is also deeply human in its fragility. It does not ask for permanence, even when it abounds. “Happiness,” wrote Jorge Luis Borges, “is frequent. It is not unknown. I say that the garden is happiness, the music. The ancient book is happiness, the smell of sleep.”

The smell of sleep—that intimate, vulnerable warmth. Vulnerable … and brief.

Like breath on a mirror, flashes of pleasure can evaporate even as they appear, their beauty sharpened by their evanescence. Pleasure teaches us to dwell in the moment, to notice without needing to hold. To let go without loss. The fleetingness of pleasure is not its flaw—it is its finest art.

There is something quiet and revolutionary about reclaiming pleasure as a form of attention. In a world that demands urgency, efficiency, and noise, the act of lingering—over flavor, scent, texture, intimacy—is subversive. Audre Lorde said:

The sharing of joy... whether physical, emotional, psychic, or intellectual, forms a bridge between the sharer and the one who receives.

To dwell in pleasure is to open oneself to intimacy, to communion, to the small, fierce joys that make living not only bearable but luminous.

Pleasure, then, is not an indulgence. It is a way of attending to life. A way of saying yes to this brief and astonishing experience of being here, now, inside this singular body, under this singular sky.

Pleasure is the poetry of embodiment. Pleasure reminds us that to feel deeply—to pause, to savor, to say yes to the world—is a worthy endeavor.

In the end, maybe that’s all we can ask of beauty: that it return us to ourselves, and then to one another. That it open the door to gratitude and deepen the quiet places of our lives with a richness we did not know we were missing.

As for the context of writing, maybe pleasure is not the story. Maybe it is the punctuation—the soft comma, the breath, the semicolon that keeps the sentence going. And in that way, it saves us, again and again, by inviting us to hover in what is now, what is always available to us in the impermanence that stretches between, but also encompasses, both past and future.

This week’s poem by Tony Hoagland captures, I think, some of pleasure’s complexity. I hope it inspire us to also explore the textural quality of pleasure, including its subtlety and even its weight, its price.

For me, this week’s poem is also about the relationship between pleasure and surrender (including to pain) from what feels like a Buddhist perspective, which would make sense, given Hoagland’s own Buddhism.

This exploration of how pleasure requires surrender excites me, because this is the kind of texture I hope to express in my own writing. It’s the richness I want to capture in the way I “do language.”

Let’s see what we reveal this week—let’s see what mosaic of meaning forms, or begins to, as we arrange our words in the direction of these ideas.