How Setting Exerts Force Not as Metaphor But Mechanism; Come Write With Us!

The Power of Place | Week Two | A Place Where Something Goes Quietly Wrong

We’re looking this week at an explosive place-based excerpt by one of my favorite writers, where place absolutely exerts its force. Where place itself is so integral to what’s happening that if we’re not watching for place, we wouldn’t necessarily think about it at all.

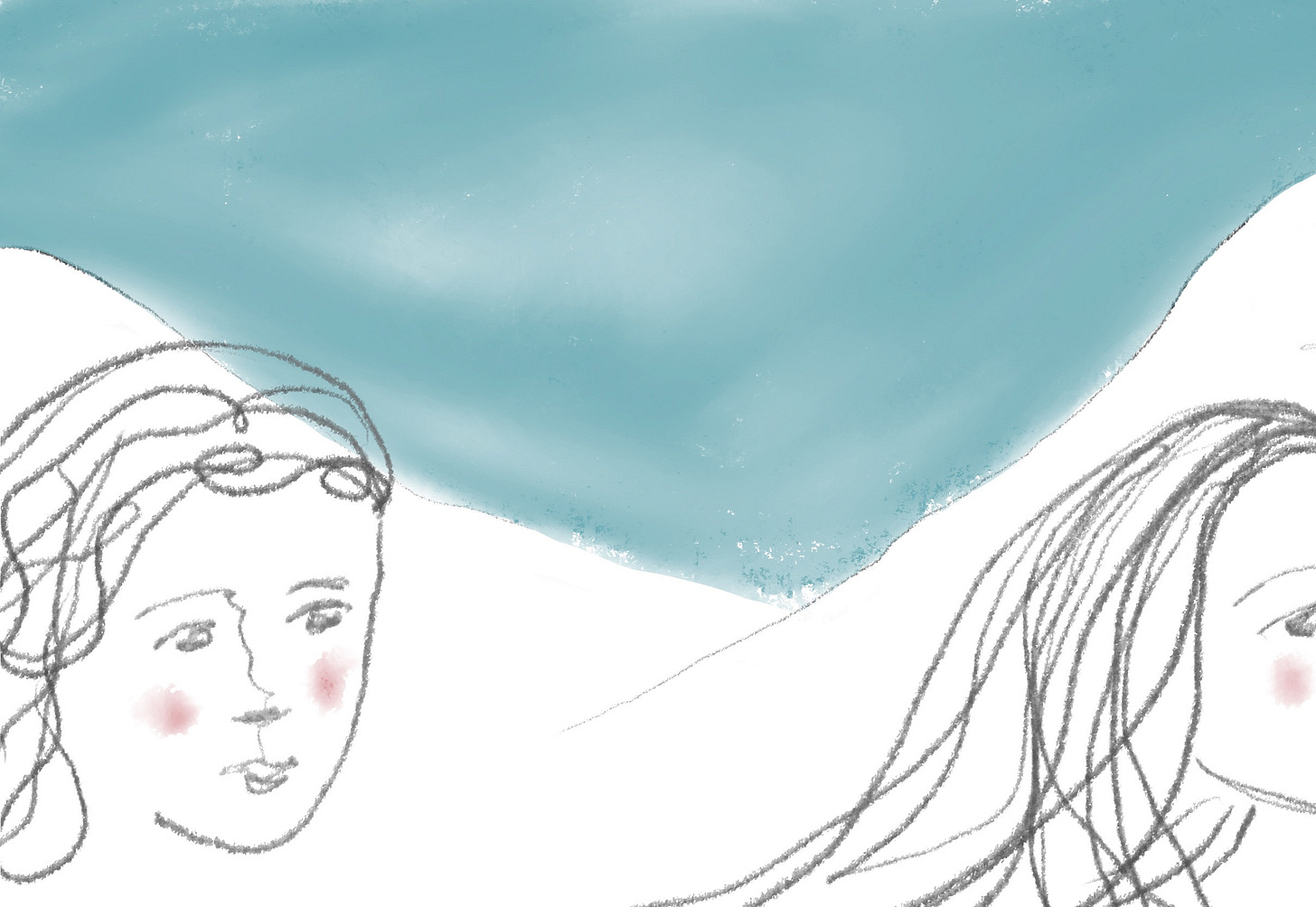

It’s from a coming of age story about the psychological and emotional growth of the protagonist from youth to adulthood, and it focuses on a crucial and pivotal interaction. The scene is quietly brutal: a snow-covered ravine, a false innocence of play, and psychological violence masked as childhood friendship. The setting—icy, muffled, treacherous—doesn’t just mirror the protagonist’s alienation and vulnerability; it enables betrayal. The landscape itself becomes complicit.

We’ll try a writing exercise inspired directly by this scene. So if your own writing tends to explore the inner life—human psychology, growth, emotion—this excerpt and exercise will be helpful in demonstrating how place can surprisingly lend a hand in that endeavor. How place can act as a quiet but potent container exerting itself on your story without us necessarily thinking about “setting.”

And that, ultimately, is a sign of writing place at the highest skill level. So integral that we don’t even see it—its power simply is.

Finally, before we move on, just want to say that your writing from last week is phenomenal! I am still reading my way through the snippets and will continue to do so today. They’re absolutely marvelous and if you haven’t read them yet, I highly encourage you to treat yourself!

Back in early 2024, when I was writing from the Florida Panhandle on the Gulf of Mexico, a place that had been devastated by Hurricane Michael just a few years earlier, I wrote:

Place sculpts our lives and our stories. Rolling hills frame perspective, mudslides threaten neighborhoods, forests breathe both life and fire, and the snowpack’s depth brings bounty or devastation. Forever, I’ve considered how cold weather can collapse us into ourselves, shriveling our skin and hardening our hair, while warm weather can unfurl our bodies, loosening our limbs and stretching our breastbones open like wings. Place tunes our speech—lengthening the sounds of our vowels or clipping them, sharpening our consonants or muddying them. And, oh, what place does to our hearts—pries them open, ignites them, softens them, shatters them. We carry place inside ourselves, too: places where we were born and where we gave birth. Where we hung from the monkey bars until our hands tore open, and where we watched our parents break each other. Where we swam naked in the moonless dark, and where we last saw our father years ago.

Dorothy Allison’s writing on place is some of the best-known craft writing on this topic. In an essay originally published in The Writer’s Notebook: Craft Essays from Tin House she said:

I cannot abide a story told to me by a numb, empty voice that never responds to anything that’s happening, that doesn’t express some feelings in response to what it sees. Place is not just what your feet are crossing to get to somewhere. Place is feeling, and feeling is something a character expresses. More, it is something the writer puts on the page—articulates with deliberate purpose. If you keep giving me these eyes that note all the details—if you tell me the lawn is manicured but you don’t tell me that it makes your character both deeply happy and slightly anxious—then I’m a little bit frustrated with you. I want a story that’ll pull me in. I want a story that makes me drunk. I want a story that feeds me glory. And most of all, I want a story I can trust. I want a story that is happening in a real place, which means a place that has meaning and that evokes emotions in the person who’s telling me the story. Place is emotion.

Place is emotion.

What an incredible, simple sentiment. So helpful. I really want us to remember this week that place is emotion. But, I also want us to remember that emotion is not usually best expressed as … emotion. Emotion is usually best expressed through concrete specific details that conjure pictures in our readers’ minds, pictures that evoke emotion.

Here’s a short example of a writer—Kendare Blake—doing, I think, what Dorothy Allison says to do: writing about place in a way that starts to scratch through the veneer, goes beyond atmosphere and description to uncover the layers where character and setting meld to evoke emotion:

Over the course of my life I've been to lots of places. Shadowed places where things have gone wrong. Sinister places where things still are. I always hate the sunlit towns, full of newly built developments with double-car garages in shades of pale eggshell, surrounded by green lawns and dotted with laughing children. Those towns aren't any less haunted than the others. They're just better liars. —from Anna Dressed in Blood

At first, Blake is abstract—shadowed places where things have gone wrong, sinister places where things still are. But then, we move onto the newly built developments, the double-car garages in shades of pale eggshell, the green lawns and laughing children. These concrete specific details are already evoking certain feelings in me so that by the time Blake says these places aren’t less haunted than others, they’re just better liars, it feels earned.

Billie Oh, my youngest adult child who is also a writer and who helps me with this Substack, studied early childhood development in college. They often consider their son Z’s life through an environmental lens, as they once explained to me that in child development, environment is considered the “third teacher.” It’s a concept that makes immediate sense to me.

Change a child’s environment—add safety gates or step stools, lower shelves to child height or raise them, cover the floor with a rug or leave it bare, add or remove curtains, color the walls bright green or pastel pink—and everything else changes along with it. This is obvious, but sometimes forget how place limits and stimulates our own behavior.

Yet, when we forget about place in our writing, it’s like leaving our characters in a white box, and then occasionally having a chair or lamp or building pop into view out of nowhere.

Back during the Story Challenge Week Three, when we were studying place, I shared that novelist Clint McCown calls place the “hydrogen atom of fiction, the atom returned to its most basic form.” He said this during a lecture at Vermont College of Arts when I was a grad student there completing my MFA in fiction. It was the best lecture on place I’ve ever heard, and the only place it’s available to the public is in Clint’s craft book, Mr. Potato Head vs. Freud: Lessons on the Craft of Writing.

Anyway, in the lecture, Clint—who is a brilliant lecturer—says:

Think of the most archetypal of the Old Testament stories. If Adam and Eve aren’t in the garden of Eden, they’re just another bickering couple—setting establishes their stakes and lends significance to the actions of both characters. What is Noah without a flood? Just a deranged shipbuilder—it’s setting that makes him a great preserver of life.

Clint also speaks incisively about the urgent importance of concrete specific details to bring place to life, to make it memorable. Something I’ve written about before. If you want a review of this powerful, consistently crucial tool, you can find that in the first post of the Essay Challenge, The Things Themselves, with its shimmers/shards exercise, or in the Eleven Things post here.

Clint puts it this way:

The simple fact is that abstractions evaporate quickly from a reader’s mind; if you want your ideas to last, you need to house them in something concrete, something the mind can picture, because if the mind can see it, the mind can hold onto it. Concreteness is the strongest housing for a principle or idea, and abstraction is weak… even when it’s right.

Finally, Clint reminds us that setting is “never just a static backdrop against which a story plays out. It is active participant in the story, a dynamic element. A quick scan of the TOC of short story anthologies will reveal titles that include settings.” Setting, Clint says, should “not be in the background, it should be something a character has to contend with.”

The real magic of writing place is to write it so well that instead of asserting itself as “place” it simply melds with the fabric of the story in ways that make it inextricable.

This week’s exercise explores how setting can carry threat—not as metaphor, but as mechanism. In Atwood’s story, what happens in the snowy ravine is a turning point shaped and enabled by the landscape. The environment appears passive, even beautiful—but it is a quiet conspirator in the events that unfold.

Writing Exercise: “A Place Where Something Goes Quietly Wrong” — a micro story in 5 steps

NOTE: If you don’t feel like writing about something that went wrong this week, simply flip this exercise to one in which you explore something that went quietly right, or a release occurs, or some kind of quiet catalyst that change’s a character’s trajectory.