I Like Doing Things That Scare Me

"The best moments usually occur if a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits" ~Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

We’re already on week five of six for our Writing Toward Pleasure intensive! I can’t believe we’ll finish next week. But I’m also incredibly excited to begin our Power of Place intensive. So, this week’s exercise is something of a bridge between these two intensives because—as is always true—nothing is ever just one thing.

Especially in writing.

Speaking of writing. We talk all the time about how the act of writing is, at its core, an act of attention. What we haven’t talked about nearly as much, or maybe at all, is how attention itself can be deeply pleasurable.

Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, in his research on flow, found that people feel most alive when they are fully immersed in an activity. “The best moments in our lives,” he wrote, “are not the passive, receptive, relaxing times... The best moments usually occur if a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits.”

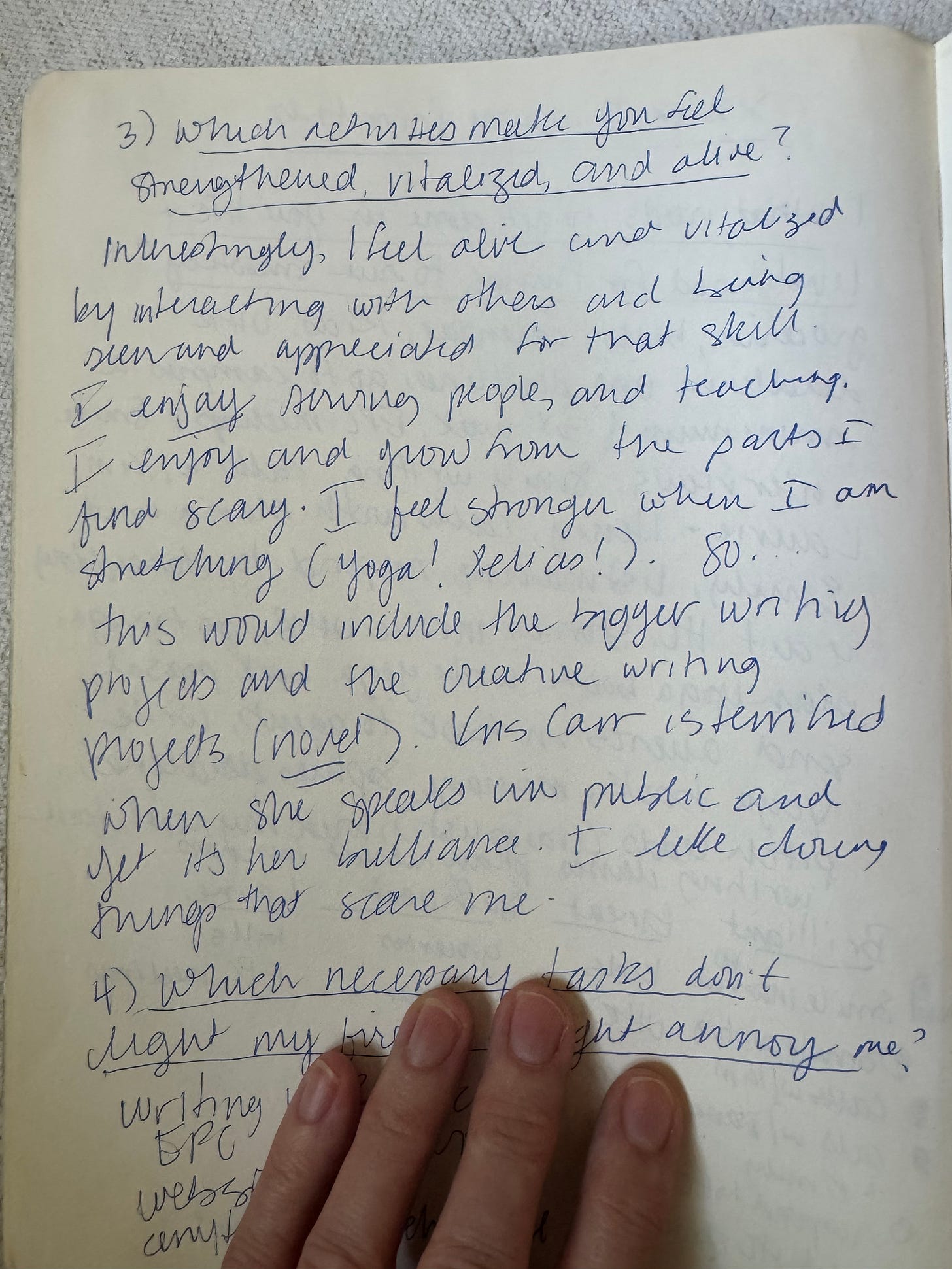

This part about stretching to our limits resonates with me immediately. In those old notebooks I found recently—the ones where I was working through Danielle LaPorte’s Fire Starter sessions, I wrote—in response to the question, “What activities make you feel strengthened, vitalized, and alive”:

Interestingly, I feel alive and vitalized by interacting with others and being seen and appreciated for that skill. I enjoy serving people, and teaching. I enjoy and grow from the parts I find scary. I feel stronger when I am stretching … I like doing things that scare me.

I know myself well enough to know that one reason I feel alive when engaged in activities that stretch me, and even scare me, is that these activities require my full attention, my full presence.

And writing, done with engagement and care, offers exactly that: the focused satisfaction of making something out of nothing. Making something out of nothing is, in turn, more pleasurable when we allow ourselves to take pleasure, real pleasure, in the words themselves. Not just what they mean, or the story they might tell, but the words themselves: their sound, rhythm, texture, and specificity. And when we do that—take real pleasure in the words and in the way the edges of the words fit together—we invite readers into this state of flow as well.

Annie Dillard describes writing as “fashioning a text... with all the care and fascination you would expend on a bonsai tree.” That fascination is a form of pleasure, and it sharpens our perception of the world outside the page. The more we seek the small satisfactions of the work—a perfectly chosen word, a sentence that lands with clarity—the more we begin to notice the overlooked pleasures of ordinary life.

Philosopher Iris Murdoch argued that art teaches us to “pierce the veil of selfish consciousness and join the world as it really is.”

Writing about pleasure is not escapism; it is a deliberate act of seeing. This can mean capturing the quiet satisfaction of folding warm laundry, the comfort of shared silence, or the beauty of light falling unevenly across a table. It makes the familiar new. Psychologist Ellen Langer calls these simple acts of presence a form of mindfulness: “actively noticing new things, which puts us in the present and makes us more sensitive to context and perspective.”

Importantly, we already know very well from our work the Ross Gay’s Book of Delights that writing toward pleasure does not demand that everything be happy. The point is to engage fully, to allow language to trace the contours of experience without numbing or avoiding it. When we write with an ear for pleasure—whether it is the satisfaction of precision, the sensuality of image, or the rhythms of thought—we also train ourselves to live with greater presence and appreciation. Writer and artist Jenny Odell, in How to Do Nothing, suggests that paying attention is itself a form of resistance: “In a world where our value is determined by our productivity, simply being present is a radical act.”

Writing for pleasure, then, is another means of staying awake.

In honor of that goal of wakefulness, we’ll look this week at a poem by Elizabeth Bishop, who was, according to the Poetry Foundation, a …

… perfectionist who did not write prolifically, preferring instead to spend long periods of time polishing her work. She published only 101 poems during her lifetime. Her verse is marked by precise descriptions of the physical world and an air of poetic serenity, but her underlying themes include the struggle to find a sense of belonging, and the human experiences of grief and longing.

About Bishop’s work, poet, editor, and critic Ernie Hilbert wrote:

Bishop’s poetics is one distinguished by tranquil observation, craft-like accuracy, care for the small things of the world, a miniaturist’s discretion and attention. Unlike the pert and wooly poetry that came to dominate American literature by the second half of her life, her poems are balanced like Alexander Calder mobiles, turning so subtly as to seem almost still at first, every element, every weight of meaning and song, poised flawlessly against the next.

So we’ll immerse ourselves slowly in one of Bishop’s precise descriptions of the physical world and then, in the light of that inspiration, immerse in the pleasure of constructing something precise of our own.