I Love Broken Things (Like Me)

Week SIX | For the Joy & the Sorrow | And I say, "holy, holy"

Yesterday we opened general registration for WITD: THE CAMP!! We’re thrilled to welcome so many adventurous writers wanting to join us by the lake (and around the fire) this August. Shakespeare said, “The earth has music for those who will listen,” and Einstein said, “Look deep into nature, and then you will understand everything better," and Pamela Heyda said, “Nature gets into our souls and opens doors to hidden parts of ourselves,” and at CAMP, we plan to render the music, the understanding, and the hidden parts of ourself in language that lives and burns. We cannot wait to write with you in person. If You can take a look at CAMP here and please, send any and all questions to writing@writinginthedark.org!

As for delights. We’re halfway through our For the Joy & the Sorrow intensive, and I hope it has been as grounding for you in this tumultuous time as it has been for me. I think it’s shifting my orientation, even if slightly. Every week, your beautiful work lifts me up and helps me see the world through a lens of curiosity and possibility, which I dearly need right now. Thank you! And if you don’t happen to be following along yet, you can join anytime, it’s asynchronous and you are never too late—and you can also join us in the daily delights chat—it’s lovely there.

This week we’ll revel in essayette #75 in Ross Gay’s Book of Delights, then do some writing in response to it.

I like essayette #75—called “Bindweed … Delight?” because Gay takes something that falls into the category of ugly/unwanted/broken/disliked, etc. and actively pushes against that categorical rejection in search of some unexpected element of delight. This is the kind of incongruity and inquisitiveness that I value in the best writing—an ability of the writer to look longer, dig deeper, work harder for the image, for what lies beneath the image, for what lies beneath what lies beneath, and then also what adjoins and surrounds, until finally a more truthful picture emerges, one that might lead us to an entirely different image than the one with which we began.

One of the many things Georgia O’Keeffe famously said was:

When you take a flower in your hand and really look at it, it’s your world for the moment. I want to give that world to someone else. Most people in the city rush around so, they have no time to look at a flower. I want them to see it whether they want to or not.

This is our job as writers, too—to use language in such a way that those who read our words receive a world we’ve rendered, a clear, true world, one that, even in miniature, can contain enough complexity and precision to be seen, and to be recognized as true.

When we work in this way, almost nothing is ever just one thing. There is almost always beautiful in the broken. And as cliche as this may sound, it was in my early twenties, when I first saw the ocean, and realized that broken seashells are gorgeous, that I began to understand that I too, even in my brokenness, might be beautiful. What a transformative moment. It was truly the first time I welcomed my hurt and angry and scarred and scared and, yes, broken parts—at least a little—into my heart.

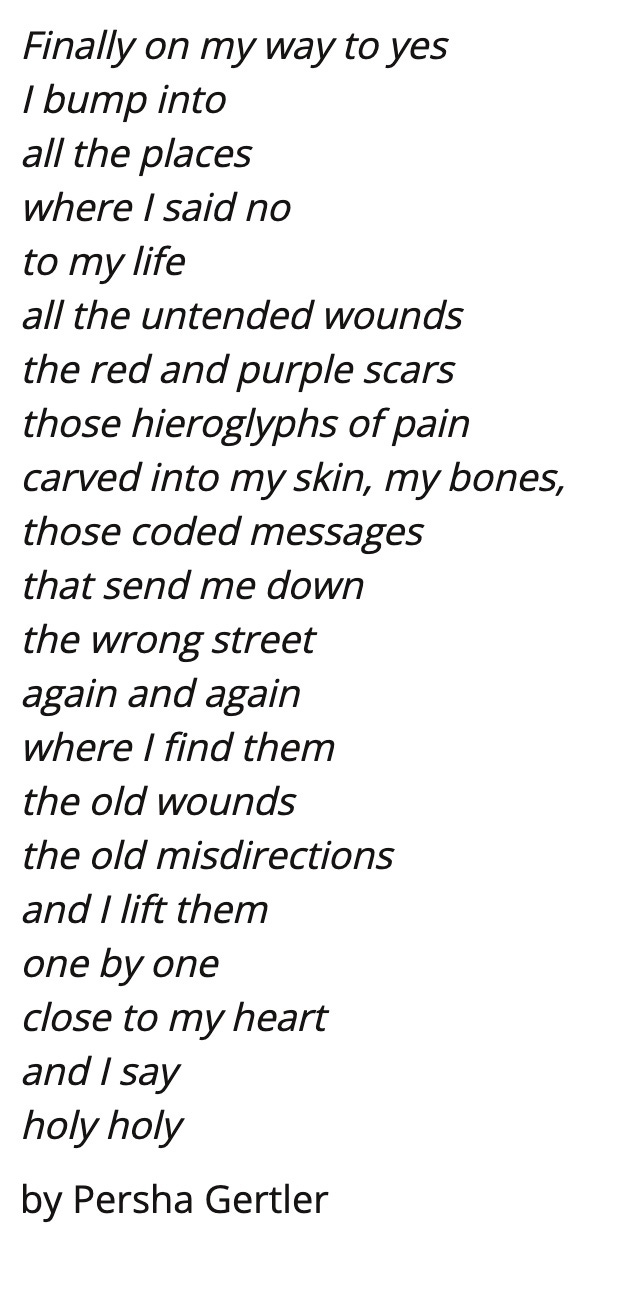

In our Write-In on Monday, I shared a poem that very beautifully expresses a similar sentiment. It’s called “The Healing Time,” by Pesha Gertler:

The writing you’ve shared from the simple exercise I offered from this poem has been quite extraordinary—you can see some of it here in the comments on the Write-In post. Meanwhile, we can look at Gay’s seemingly simple essayette about bindweed and perhaps discover something not so simple simple after all, as is always the case with Gay’s writing.

I see great resonance between my long-ago broken seashell epiphany, Pesha Gertler’s powerful poem, and this sentence that lives almost dead center of Gay’s bindweed essay:

You are right to observe in me the desire not to live with bindweed, which does not in the least negate or supersede my desire to make living with bindweed, which I do, okay.

Oh, the beauty of dialectics, the beauty in the broken, the beauty in the world and all of us, in spite of and because of everything.

I certainly did feel something at that moment in the essay, as well as when Gay puts bindweed in his pocket, gets on his hands and knees in the garden, hears the plants singing, and the last sentence.

I’ll start my close read of “Bindweed … Delight” by noting how the writer holds hands with his title and admits the challenge he’s undertaking: “There are gardeners reading this who are likely thinking that if I try to turn bindweed, that most destructive, noxious, invasive, life-destroying plant into a delight, they will