My Creative Manifesto

Things I Have Learned About Building A Newsletter During My First Two Years On Substack

Today’s archival post is the more philosophical Part Two of an earlier post about growing a creative life—essentially, this is an updated version of WITD’s first birthday missive written in the spirit of gratitude and sharing the eleven most salient things I’ve learned since launching Writing in the Dark (and, to be honest, in the thirty years of my professional life as a writer).

And to note: I didn’t include this item on the original list, but I would also now be sure to add: Be soft. Be soft. Be soft.

Substack—and the literary world and creative life in general—can be competitive and often harsh, and, yes, the path is thick with disappointment and even heartbreak. It’s also pocked with setbacks, rejections, jealousy, and, once in a while, a personal slight or two. Do not let these distractions become the landscape of your writing life. Do not let these distractions become the melody sung by your creative spirit. Do not let these distractions char the open field of your heart. Please, do not let these distractions subtly harden you to the world and all it offers up for our imaginations (thank you, always, MO). Be soft with others, be soft with your process, and be soft always with yourself. Have goals, sure, and more importantly, have some burning desire that pulls you into and through it all, including the dark times, the hurting times. And yes, measure your progress in light of your goals and desires. But do not ever define yourself by the gap between your desires and your so-called achievements. Never let that gap fool you into thinking you are not good enough, or real enough. You are. Just keep reaching with an open heart and open hands toward the light. That’s all you need to do.

In addition to being a Part Two to that earlier post, this is also a companion to my Eleven Urgent & Possibly Helpful Things I Have Learned About Writing From Reading Thousands of Manuscripts post of two years ago. I hope you find something useful here.

1. Be yourself. Whether on Substack or anywhere else, it helps immeasurably to be who you actually are, to let yourself be seen and heard for your true self, and, in that way, to write what only you can write. What does that mean? To write what only you can write? Well, only you can answer that. It is a question to dwell on, to enter into, to sit quietly (or fitfully) inside of until you feel your way to the answer. For me, being myself means a few things, which I’ll get to in a moment, right after I acknowledge what it doesn’t mean. It doesn’t mean having to write highly personal, intimate, confessional work. Absolutely not (unless you want to, then go for it! Writing in the Dark is admittedly intimate). It does mean you will benefit from writing in your own voice and from your own unique, specialized perspective in a way that no one else ever could. No one but you. It’s your voice, after all, and only yours—again, whether on Substack or anywhere else. Even if you publish lots of guest essays and cross posts, etc., your readers want to hear your voice. So, no matter the focus of your work, you will want to warm it, shape it, angle and chisel it by writing in your own fiercely unique register, tone, and timbre. It can help to ask yourself, why are you writing this, with the emphasis on you.

2. Desire determines who you become. As Maria Popova wrote in the Marginalian, “It is by wanting that we orient ourselves in the world, by finding and following our private North Star that we walk the path of becoming.” The most successful work seems almost universally to be those created by people with a blazing passion (or, at minimum, an insatiable curiosity) for the topic(s) they write about. In other words, they are fueled by desire to know, understand, illuminate, create, share, connect, etc., around a certain axis of ideas. This kind of passion and curiosity is palpable, infectious, and cannot be faked. I know that my own curious passion has helped Writing in the Dark grow quickly and well from almost nothing. This newsletter is fueled by my burning belief in the power of language as an agent of self-discovery, human relationship, deeper meaning, and collective transformation—and that energy, in turn, fuels readership. In a crowded arena, which Substack has become, passion stands out. Therefore, it helps to be writing about what you care most about.

The intersection of writing and teaching—that is, the probing of what makes good writing sing and sear and how we can achieve that in our own work, and how doing so makes us better and makes the world better—truly excites me. I knew from the jump that if I launched Writing in the Dark, I would be writing about writing and building a writing community because that’s where my desires live—that’s what I’ve always wanted and what I still want.

And, by the way, I love every chance I can get to think and talk about desire, about wanting—the verb. I love wanting, the heat and the ache of it, and the way it works, in the end, to not only fuel our creative practice, but indeed to define our lives. I believe it is the wanting we must nurture, the flames of desire we must fan, in order to sustain our creative practice over time, even when it’s hard. Also to reignite our creative practice after a necessary period of rest. We have to want it and let ourselves feel—really feel—the vulnerability of that wanting. And it is profoundly vulnerable. Wanting is always vulnerable. Which is why we—especially women (but also many men)—learn to avoid it, on the false hope that doing so will protect us from pain of not getting. But it won’t. Walling ourselves off from wanting or dulling its ache with other distractions will only distance ourselves from ourselves, which may be the worst kind of suffering of all. It’s taken me a long time to find the framework—let alone the words—for this topic. And I’m still not there, so forgive my clumsiness as I attempt to interrogate a territory as vast and dangerous as desire. I’m speaking about desire in a broad, deep sense of the word, the sense of it found in the word’s Latin root—“desidus,” which means “away from a star.” I could not love that more: the idea of our desire being a longing for a star! Maria Popova wrote gorgeously about this in the Marginalian, which is where I first learned of the etymology of the word desire. As Octavia Butler writes:

All prayers are to Self

And, in one way or another,

All prayers are answered.

Pray,

But beware.

Your desires,

Whether or not you achieve them

Will determine who you become.

3. Alignment matters. Alignment for me means being clear and intentional about what I’m doing so that I can make intuitive decisions that make sense for my personal goals, rather than find myself reeling from the constant barrage of conflicting advice about what works or doesn’t work on Substack or anywhere else. Instead of being buffeted about, I listen to my own instincts and experience when it comes to what to write or publish, how often to write or publish, how short or long to write, which images to use (or even how much emphasis to place on images/design), and, finally, if and how to paywall posts and at what rate, etc. It’s not that I’m averse to guidance. II’m not. t’s just that I don’t get overwhelmed or confused when the guidance is contradictory (which it often is) because I know what my goals are, which helps me know which advice applies to me and which advice is more suited for others with different goals. I am trying to build a beautiful place devoted to writing and the writing life, where people can ignite or re-ignite a writing practice, learn new and powerful ways to bring themselves to the page, re-invigorate their relationship with language, and find real community. When I keep this vision in mind, I tend to know what feels right and am able to let go of what doesn’t make sense for me. I am also able to confidently amend past decisions as needed when things change. Alignment is crucial for sustaining a growth pattern without burning out or getting knocked around in the constant churn of “how to succeed.”

4. Give value. Give the best value you can every time, regardless of price. Of course, value and money are often connected. But value is a far more important place to put your focus than paywalls (the questions around which seem to cause many people much angst). Some say give everything away for free—just have faith that if people value it, they’ll pay you. For some writers, like Heather Cox Richardson, this model works exceedingly well. Others believe that no one should “write for free,” and paywall everything. So what is one to do? There’s only one answer, which is that you must do what makes sense for you and for your publication, and be clear on why it makes sense. As

said last year, not all writing is ready for prime time or about topics that people are readily willing to pay for. Which is fine. Also, not all art needs to be monetized! That’s also fine. And not everyone here or anywhere needs to be hustling to make money or “grow.” It’s 100% perfectly fine to just … write and explore and enjoy and see what comes of it! Just be clear with yourself on what it is you’re doing here so that you don’t get tossed around in the waves of other people’s visions and ambitions. Be so clear you can feel the clarity right down into your bones. When you’re very clear on your vision, it becomes easier to know what to do with regard to paywalls and everything else, too, which in turn makes it easier—when it comes to advice—to take what’s useful and leave the rest. In the meantime … focus on ensuring that your writing offers something of real value. Value can be so many things. I love when people make me cry, and I love when they make me laugh. I love when really smart people educate me on topics I care about (I’ve already mentioned Heather Cox Richardson, but also, check out who writes the the fabulous and incisive , which offers intricate, informed writing on women’s health that’s well worth paying for, or Sari Botton’s fabulous Oldster, or Virginia Sole-Smith’s Burnt Toast, just for starters). I also love when people write in artful, untamed ways that make me gasp with envy and awe. Writing can be many things—but to attract readers, paid or free, it must have value.5. Embrace generosity. I’ve written about generosity before—To Have, Give All to All, or What It Means to Write (& Live) Generously. And I love the generosity of the literary community in general. Inspired by others, I seek to be the most generous writer and teacher I can be. I recommend approaching your work with a spirit of generosity in all the ways you can—and that’s as much about how you interpret the work and actions of others (gratitude and a little benefit of the doubt can come in handy) as it is about what you do and offer. And another thing about generosity: make it genuine and try not to expect anything in return. For example, I like to link to beautiful published work not just from established writers but also from emerging writers in my craft posts, because it helps their careers and it’s inspiring for my readers and my students to study work from writers who have not yet “broken out.” For the same reason, I try to share exceptional work from emerging writers on Substack, as well. It’s also good to reach out directly to writers whose work you love, and tell them so. Comment on their posts because you have something to say. Restack posts because you really want others to see them. Try not, on the other hand, to do these things with the thought of an “exchange,” with the idea that these other writers will “return the favor.” That way lies the path to counting and measuring and comparing and resentment. It’s better to promote the work of others simply because you’re an engaged reader and generous literary citizen. Although the favor economy will always be part of how things work—it’s inevitable—it’s more fun and less stressful when you try to operate from a place of real love and enthusiasm, without tracking for reciprocity. Also, when likes, comments, and shares become a naked commerce of trade rather than genuine interaction, it tends to show. Not only is this not a great look, but your endorsement loses its power because people won’t be able to trust you. So, give generously and from the heart and avoid transactionalism lest you undermine your credibility and weaken your word. Simply be generous because it feels better than being ungenerous. To have, give all to all.

6. Be brave. When I first founded Writing in the Dark as a writing program in 2012 and started registering for my first-ever week-long retreat (I had never even attended a retreat, let alone led one!), I had no idea if anyone would sign up (I described that unnerving experience in detail in an interview with Hippocampus a couple of years ago.) But the part that’s relevant now is how my friend said to me, when she saw my retreat promos on Facebook, that I was very brave. “Well, I haven’t really invested any money or anything,” I told her. “My deposit for the lodging is totally refundable if no one registers. There’s not much at stake.” My friend nodded, then said softly that it wasn’t money she was talking about, it was the possibility of me putting myself out there and failing. How that would look for me. What people would think. “Oh, yes, that,” I said. “I know, but oh well.” You see, by then, I’d already come to understand, even before I knew the name for the spotlight effect, that no one was paying as much attention to me as I might believe they are in my most self-conscious moments. I’d already made peace with the possibility of failing, which is what allowed me to offer that retreat in the first place. And by the way, it sold out. Being brave means different things to different people, but I think it almost always means being willing to try new things, make mistakes, and embrace failure. It really is okay to fail, I promise. Remind me to tell you about the time, many years ago, when I had a nonfiction book deal with Simon and Schuster and my cowriter and friend called me to tell me, after a call with her agent, who’d just spoken to our editor, “Jeannine, she hated it. I mean, she really hated it.” Guess who’d done most of the writing at that point? That’s right. I had. Anyway, the contract was killed and the book never happened. I share this to counterbalance the retreat story. Not every story of risking failure ends happily. But I am still here, still writing, still being brave. Ultimately, as you’ve heard before, courage is about letting ourselves be afraid and doing things anyway. I love that venn diagram meme that shows where the magic happens (far outside of our comfort zone). I remind myself of it all the time, and then I keep going.

7. Write beautifully. What it means to write beautifully will vary depending on the topic and genre of your newsletter. In some instances, beauty might simply mean writing that is clear, factual, easy to read, and high value. My genre is creative and literary, so I work hard to ensure that even in my teaching posts on Substack, even in posts like this one, I find a way, in at least one or two lines, to show what I mean when I say good writing. I see my newsletter as different from my essays and stories in journals or books, because the pace is so fast, for one thing (I publish about 5 times a week!), and the newsletter genre is just a different beast, for another. So not every post in Writing in the Dark is going to be a literary masterpiece! But I do strive to play with language and make it clear that I care about writing and am trying always to touch something, somewhere in the writing that might wring you out and leave you in a heap in the basin of that old porcelain farm sink where you once stood to rinse the sour milk from sippy cups, where you stared into space toward the end of another marriage, another life, the life of a previous self whose next chapters you will never know.

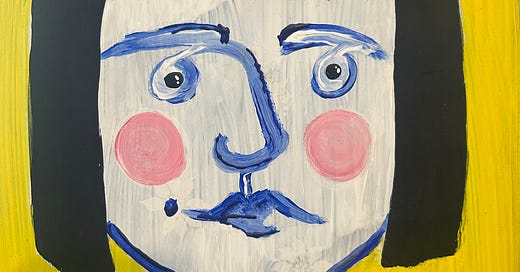

8. Allow for ease. In yesterday’s nuts and bolts post about how I grew Writing in the Dark, I strongly emphasized hard work. And that’s true. However, and this is a big however, it’s also true that I’ve allowed for ease in a lot of crucial ways. And allowing for ease has made this project sustainable and joyful (even if tiring) rather than just a chore. Ways in which I’ve allowed for ease are myriad. For one thing, I let myself be nerdy and write about things I love, which is easier than writing about whatever I think I “should” be writing about. Once when I was struggling with some family stress and couldn’t bear to write the Monday post, I wrote about injured beavers falling in love instead, and it was one of my post popular posts last fall. I also reject perfectionism and refuse to beat myself up over typos (I’m writing thousands of words a week and don’t have a copyeditor or a proofreader—there are going to be typos). I also don’t get too bound up over the appearance of the newsletter, and went for two years without any real design—only last week did we unveil

’s new illustrations for WITD! (I particularly love today’s drawing). But until now, I just couldn’t get to any kind of place where design could get prioritized. And that was good enough, too. I guess for me that’s the central definition of “allowing for ease,” which is to say I don’t always have to set the bar beyond my own reach. That’s so mean. Making the thing unattainable for ourselves just creates frustration and a feeling of never being or doing enough, which leads to dis-ease. So I choose ease instead.9. Make friends. We’re in the midst of an unprecedented epidemic of loneliness in America. It’s hurting our health and diminishing our spirits. So, yes, I could have said “build community,” but isn’t the idea of making friends more enticing? Some of my closest friends—almost all of them—are people I’ve met through writing and teaching. And aren’t friendships part of the connective tissue that holds community together? And isn’t it possible to make new friends at any age, and quickly? Why not? It’s what we’re here on Earth to do. I mentioned yesterday that I respond to comments, reply to emails, comment on and share other writers’ work, etc. And that’s all part of fostering a vibrant, engaged community of subscribers. But there’s so much more to literary community than “subscribers.” It’s about relationships and synergy. It’s about human connection, and the fragile threads that stretch between one life and another. I make a point of reaching out to other writers via email to ask about deeper collaborations or to express my awe when their work deeply moves me. And I love when other writers reach out to me. We’re in this together and there’s a buoyancy and lightness in lifting each other up. Last week when the beloved writer and extraordinary literary citizen Gabe Hudson died, I paused to read everything that everyone posted about him, even though I did not know him personally. Why? In part to honor his life, and in part because I want to live in the way he did, wherein I try to be a friend to everyone and allow for friendship to happen with ease in all of my interactions. In Jane Ratcliffe’s poignant posthumously published interview on Beyond with Gabe this week, he said:

I am nothing if not a litany of the kindnesses that others have shown me: every great thing that has happened in my life is the result of someone’s kindness and generosity of spirit. Because I know how life-altering kindness can be, I try to pay it forward every chance I get.

That’s how community is built, yes, but more importantly, it’s how friendships are made. I’m here for that.

10. Be curious. As Einstein said, “The important thing is not to stop questioning. Curiosity has its own reason for existing. One cannot help but be in awe when he contemplates the mysteries of eternity, of life, of the marvelous structure of reality. It is enough if one tries merely to comprehend a little of this mystery every day.”

If you’re intrigued about the workings of curiosity and the power of a question, consider consider this passage written by the daughter of the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget:

Where does that little baby come from? I don’t know. Out of the wood. Are you dust before you are born? Are you nothing at all? Are you air? Babies don’t make themselves, they are air. Eggshells make themselves in hens. I think they are air too. Pipes, trees, eggshells, clouds. The door. They don’t make themselves. They have to be made. I think trees make themselves and suns too. In the sky they can easily make themselves. How is the sky made? I think they cut it out. It’s been painted.

And isn’t a community you create on Substack or anywhere else a wonderful place to ask questions, to be ravenously, endlessly, delightfully curious? About the things we write about, yes, and about how to develop and grow your newsletter, sure! But also about every little thing that makes the world turn, that makes you you and me me, every little crevice in which intersections occur within this world we all share, every little granular detail you notice on your way through the checkout lane at the grocery store when the person behind you is quietly sobbing and the rain hasn’t let up and your daughter still hasn’t returned your message and you’ve begun to wonder how it is that you landed here as a middle-aged woman with a cart full of disposable diapers and canned cat food neither of which are for you. Listen, curiosity is the root of empathy, and empathy, in turn, lends depth, complexity, and emotional resonance to our writing. It’s no wonder, then, that I was so moved by what Maria Popova of the Marginalian wrote recently when discussing George Saunders and his invocation for us to love the world more and have courage for uncertainty. Popova said:

Nothing, not one thing, hurts us more — or causes us to hurt others more — than our certainties. The stories we tell ourselves about the world and the foregone conclusions with which we cork the fount of possibility are the supreme downfall of our consciousness. They are also the inevitable cost of survival, of navigating a vast and complex reality most of which remains forever beyond our control and comprehension. And yet in our effort to parse the world, we sever ourselves from the full range of its beauty, tensing against the tenderness of life.

11. Be grateful & celebrate. This might be my favorite lesson, and it’s one I’m still learning and practicing, even now, as I share this celebratory Writing in the Dark two-year birthday post of the most salient lessons I’ve learned. Did I hesitate before pouring my heart into a two-part missive on the growth of Writing in the Dark? I sure did. Posts like these can seem boastful, like “look at me!” ploys, like attention grabs—all of which are perennial topics in Substack Notes. I don’t want to be seen that way. No one does. On the other hand, this path we’ve chosen, that of living a creative life and, in my case and many others, supporting ourselves (or trying to) in creative fields, is arduous, lonely, and rife with rejection and disappointment. With heartbreak, even. It can be a bitter, demoralizing, and sometimes even dehumanizing journey, the journey of the artist, a paradoxical truth if ever there was one, since art itself is so life-giving, and in some ways more accessible than ever before. As Laura McKowen said recently on Notes, this is a very exciting time to be a writer! But that doesn’t mean it’s easy. It never is. Therefore, I’ve come to believe it is quite necessary to celebrate as many of the small, medium, and large milestones as possible. I am a person who celebrates second-place finishes and honorable mentions, who sends my friends texts and screenshots of “warm rejections.” In fact, I even celebrate submitting my work (yay, me! I finished something!) and entering contests, well before I know whether my efforts will land. I don’t celebrate all these things publicly, necessarily, though I do appreciate when other writers post about completing their NEA applications or querying agents, and I make a point of cheering them on. And when people post about their rejections? No one’s celebrating rejections, per se, but we are wise to count them as accomplishments, because they prove we’re working, trying, engaging, taking chances. And besides, even commiseration is a form of validating each other’s efforts and making space for each other’s humanity. The creative path is no gentle woodland stroll of dappled light and cedar-scented breezes. It can sometimes feel more like a hot humid walk through a crowded chicken coop with no shoes on. Or something like that, I’m not a farmer. The point is, life is short and already prone to a deficiency of joy. But we do have the option and perhaps even the obligation to notice and applaud the moments that, taken together, add up to a trajectory toward success. See what I did there? Trajectory toward success? It’s not about the finish line of “success,” which is an ever-moving target we will never reach (just ask anyone who’s ahead of you about the way that so-called finish line edges forward with each new accomplishment). No, it really is about the here and now, and the progress we’re making as we trudge along. If we don’t celebrate the many soggy steps between here and the unattainable “there,” we’re missing, well, everything.

Love,

Jeannine

PS I know I’m repeating myself, but For the Joy & The Sorrow writing intensive is still going strong, and is so lovely. If you are not a paid subscriber, I hope you’ll consider becoming one to help us raise a continuing chorus of complicated delight in a harsh world.

Jeannine,

I cannot tell you how prophetic your message was for where I am right now in my creative journey. Thank you is a trifling way to let you know that I felt I was drinking from a fount of generosity and kindness when I read it.

You see, I have been so mired in doubt and discouragement, because I have worked so very hard these last five years to grow as a writer (and as a person). I've taken myriad courses and workshops on aspects of craft and skill but also on understanding the marketing piece and preparing a query and book proposal. I have hired consultants and independent editors to go through my work line by line. I have incorporated their feedback. And still...nothing. No break in to the mainstream industry. At all.

People tell me to read the literary magazines I want to be published in. That's just the problem: there are far too may from which to choose, and I don't generally read periodicals. I read BOOKS. I devour long-form writing, not usually shorter pieces. But when I DO read what pieces have won literary awards and contests, I am further discouraged, because most of the time, the quality of my writing is (what I would say, hopefully not arrogantly) about on par with what is being published.

I can tell myself I am a good writer. I can continue showing up every day (and I do) to sketch an early draft, revise a piece I'm developing, or schedule an essay to be published on my Substack, but it doesn't seem to make much of a difference. It matters a great deal to me if what I'm working on doesn't land or isn't received. It's like Madeleine L'engle wrote about the need for our work to be published: it means the "vision has been communicated." Exactly.

I feel like my vision has fallen short or flat, and I can't figure out what I have done wrong.

I am telling you this, because your post today spoke into this wound of mine--the wound of rejection and inadequacy--and I needed it. I needed to be reminded of why I write, what I am passionate about sharing, and I guess just...keep doing it? The thing is, I'm not sure how sustainable it is for me to keep writing without ANY sort of financial compensation before I need to seriously consider getting a different (paying) job.

Maybe it's all exacerbated by the fact that I used to have a nice, cushy income as a freelance writer and public speaker before I walked away from the religious writing I was doing. Going from that to nothing is harder than never knowing what it could be like.

Sorry this was so long.

Jeannine … I love this. Thank you for being such a bright light. I feel so fortunate to have found WITD and you. Though I am not always able to plug in 100%right now … I’m learning so much from you.