Source Waters

A 7-step writing prompt exploring the big shapes that foreshadow our lives + an experiment with voice + a closer look at what's wrong with the old adage about sensory detail and how to do it better

We all come from somewhere. And entangled within and between us—carried in the infinite possibilities of our genes, in the stories that came before and persist inside us—is a map to that where. To that there. To that there there as Gertrude Stein once referred to it when speaking of the loss of an original somewhere (Oakland as she once knew it), a phrase Tommy Orange later and brilliantly repurposed as the title of his unforgettable novel, There There.

For this week’s 7-step writing prompt, we’ll explore our own somewhere through an origin story. It’s a complex prompt, and it’s not necessarily an easy one, but I’ll walk you through it step-by-step as best I can (and if you wish to skip this preamble and go straight to the prompt—which I really don’t recommend this week—just scroll to the bolded subhead Writing Prompt: Source Waters).

We have, in essence, a tap root that drinks from a kind of potent source water—a source water that moves in our blood, no matter how far we travel. George Ella Lyon pays homage to this central truth in her poem (and related writing prompt) “Where I’m From.” I’ve taught the poem and prompt many times with consistently interesting and sometimes genuinely beautiful results, including from beginning writers and even those who see themselves as absolute nonwriters. I think that’s in part because of the prompt’s crystalline specificity. But I think it’s also in part because of the way the prompt connects writers to their source water.

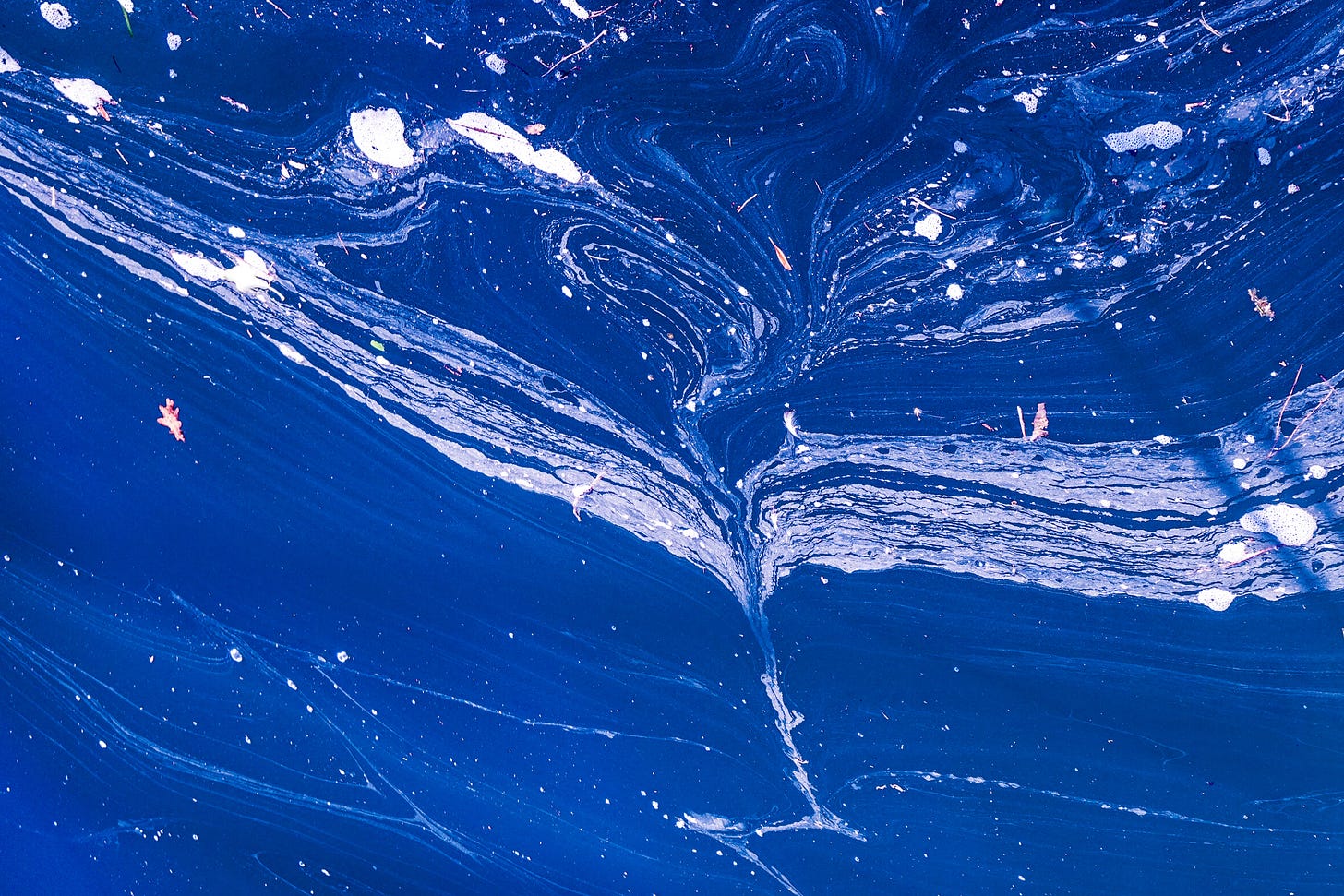

Source water.

What do I mean by this? I mean, I suppose, the question of who we really are. Which is the question that all writers, or at least those engaged in a serious practice, must eventually confront. The question of who we really are under all of the masks and costumery and white noise of our daily lives. If that’s the question, then tapping into our source water can lead us toward, if not answers, then possibilities (which tend to be richer and more fascinating than “answers” anyway).

Source water is teeming with old, old stories, decomposed stories, perfectly preserved stories, haunted stories, misleading stories, life-saving stories, all sodden and slick with the algae that flourishes in the deepest recesses of this amniotic place where our ancient myths swim. And although some of the old stories are surely distorted and incomplete, even these are still (and perhaps especially) worthy of our curiosity. Worthy of being pulled up to the surface for closer examination. We are narrative beings, story-making creatures, and our origin stories are living organisms that give us—and the new stories we give rise to—movement, gravity, and light.

Just listen to how this kind of movement, gravity, and light sound in the origin story with which Barbara Kingsolver begins her Pulitzer-winning novel, Demon Copperhead:

First, I got myself born. A decent crowd was on hand to watch, and they've always given me that much: the worst of the job was up to me, my mother being let's just say out of it.

On any other day they'd have seen her outside on the deck of her trailer home, good neighbors taking notice, pestering the tit of trouble as they will. All through the dog-breath air of late summer and fall, cast an eye up the mountain and there she'd be, little bleach-blonde smoking her Pall Malls, hanging on that railing like she’s captain of her ship up there and now might be the hour it's going down. This is an eighteen-year-old girl we're discussing, all on her own and as pregnant as it gets. The day she failed to show, it fell to Nance Peggot to go bang on the door, barge inside, and find her passed out on the bathroom floor with her junk all over the place and me already coming out. A slick fish-colored hostage picking up grit from the vinyl tile, worming and shoving around because I'm still inside the sack that babies float in, pre-real-life.

The full excerpt of chapter one is free and worth immersing in fully. But, for now, I’ll simply say wow.

And again, wow.

Let’s look at what’s working here.

First of all—that voice. That outrageous, maximalist, unrelentingly commanding voice. Immediately, this narrator establishes his bold vocal signature and sustains it. Second of all, even in just two paragraphs we receive a ton of information about this character and where he came from and what that might mean for who he will become. Lastly, these opening pages are built of the kinds of concrete, specific details that, one after the other, make clear that they matter to the story, both in the moment and likely later. These details make clear that they are more than decoration, or atmosphere, or the result of “adding in some sensory detail” (which, for me, exemplifies the kind of overly vague writing adage that sends beginning writers astray). Sensory details are not window dressing that we can just “add in” to improve a story. Concrete specific details (often sensory) should be essential to the meaning and aboutness of a piece. They should matter. They should stem from the story’s own source waters!

Which brings us to the idea that if origin stories are like the source-code of our understanding of ourselves and others, then concrete specific details are the building blocks of that source-code. We know that our lives are mysteries best understood in reverse. And the purposeful excavation of and crafting the details of our origin stories can lead us to revelatory hindsight by dragging us through into a mysterious, watery world of why.

Isn’t why a wonderful question? We should always ask why, even if we can never fully arrive at an answer. What we can arrive at, if we are lucky, are the big shapes that long ago cast their shadows over our present-day lives. That is to say, our lives were always, since before we arrived, foreshadowed. And the human journey is made richer by searching for the sources of those shadows.

So let’s search.

But first I want to clarify something. And I hope this hurts no one’s feelings—because I am a mom and I treasure my three birth stories so much I even wrote them all into The Part That Burns. But the truth is that many modern hospital births are quite similar to each other and do not foretell, as Demon Copperhead’s birth did, the future shape of a life. Therefore, I want you to be very careful when working this week’s prompt not to be too literal about the word “origin,” which is why I am using the term “origin story” not birth story.

As I mentioned earlier, George Ella Lyon’s “Where I’m From” gets at some aspects of what I am saying here, because she focuses clearly on concrete specific details of origin stories. Some such details will inevitably be people, like parents or other family members (which we certainly see in the Demon Copperhead excerpt). Most likely, the actual mechanics of your birth will likely not be particularly relevant to your origin story, but as you’re working the prompt, you should feel free to identify a few of those kinds of details and include them if they seem important. However, a more helpful way to consider origin stories might be through superheroes. Every superhero has an origin story that made them who they are. First, they were born, then something happened, then they became something else entirely. If mining your birth or early life don’t reveal anything electric and exciting maybe widen your scope and think about all the different origins you may carry inside yourself.

Now, let’s step toward into our own shadows with a complex, seven-part writing prompt designed to help you excavate and arrange something resembling the opening pages of the novel of your life. This will be hard, but also fun. And to note, you can approach it as fiction or creative nonfiction. It doesn’t matter in this case. The craft will be the same, and you’ll learn something about yourself and grow as a writer either way. You’ll certainly come away with some practice with voice. And you should end up with something interesting on the page.

Let’s begin.