"Tear apart everything above ground—everything—and most plants can still grow rebelliously back from just one intact root. More than once. More than twice." ~Hope Jehren

Visceral Self: Writing Through the Body | Week Two | Root: My Body, My House, My Horse, My Hound

Visceral Self: Writing Through the Body dates to note for founding members (you can manage/upgrade your membership here). And for all paid members, we’ll also be hosting impromptu silent group writes on Zoom (times announced soon). We’re excited to write with you!

🗓️ 🕯️Wednesday May 1, 8 PM CT, Live Candlelight Yoga Nidra Meditation for Founding Members on Zoom (Zoom link emailed an hour ahead)

🗓️ 🕯️Wednesday June 12, 8 PM CT, Candlelight Yoga Nidra Meditation for Founding Members on Zoom (Zoom link emailed an hour ahead)

🗓️ 🕯️Friday June 21, 1 PM CT, Celebratory Live Solstice Salon for Founding Members on Zoom (Zoom link emailed an hour ahead)

Writers, you raised the roof last week with your outpouring of visceral writing.

Our Week One post is bright with your gorgeousness and ablaze with your humanity, as is last week’s Thursday Thread on our relationships with our bodies.

Thank you, thank you, thank you, and thanks also to the more than forty of you who attended the live yoga nidra session last Wednesday. It was beautiful to share that experience with you.

Now, a few housekeeping notes & clarifications:

A few of you have mentioned being “late” to post your work in the comments—but you are not late! It’s true that if you are able to post your work on Wednesday or soon after, you’re more likely to catch me there with you in the comments, responding, interacting, offering observations and clarifications and encouragement. But the comments stay open indefinitely for you to work at your own pace (and I do circle back to read work throughout the week and beyond, because I enjoy your contributions very much!).

You can easily find the posts for this intensive in our Visceral Self section or by using our Curriculum Index.

We also recommend making sure you elect to receive your Writing in the Dark posts by email. You can, of course, use the Substack app, but we hear from more members trying to find things when they’re on the app alone vs. allowing for email settings.

- ’s audio and video offerings are now collated into one stand-alone catalogue for founding members, which can always be accessed via a button on this post, like this:

Note that resources in the Founding Member Meditation Guide will include the whole set for the intensive so far (so at present, resources for Week One and Week Two, in order; next week we’ll add Week Three, and so on).

Each week will vary, but in general you can expect recorded reading of the week’s poem or excerpt, and verbal instructions for the writing exercise, so that you can listen to both while you are in your yin yoga pose. If you’re not using Billie’s audio, you can read the writing exercise/prompt a couple of times before you settle yourself into the yin yoga pose (if you are doing the pose), so that you can write immediately when you come out of the pose.

Straight from pose to page—that’s how we teach this curriculum in person, and how we recommend you approach it at home, if possible. However, we won’t ever let perfect be the enemy of good.

There are a million right ways to do this, and you can choose the one that works best for you each week.

Now, for some inspiration before we work, let’s focus for a moment on what embodiment can do for our writing on the whole—what it can do to bring our work alive. Malina Moe, in her recent essay, “There Is No Point in My Being Other Than Honest with You: On Toni Morrison’s Rejection Letters,” published in Los Angeles Review of Books, touches on this question when she explores the feedback Toni Morrison provided in her incredibly generous rejection letters. Moe writes (emphasis mine):

Editorial advice often boils down to show don’t tell, and literary critics like Ted Underwood, Andrew Piper, and Sinykin have argued that the language of sensory and embodied perception sets fiction apart from other genres, like biography. Morrison’s letters often bear this out. In 1979, she informed one writer that their “story is certainly worth telling,” but they “describe people and events from a distance instead of dramatizing them, developing scenes in which the reader discovers what kind of people they are instead of being told.” Vivid scenery and precise details offer readers room to maneuver, a way to discover a world that resonates. A couple of months earlier, she gave similar advice to a young Bebe Moore Campbell (who went on to become a best-selling author). And, addressing one colorful character who had evidently dropped by the Random House offices unannounced to pitch their memoir, Morrison warned about conflating an eventful life with a well-crafted story. “Your manuscript was no less interesting than you were,” she noted; however, to make it publishable, “you would have to add the artifice (or art) that you said you decidedly would not do.”

I loved reading this essay about Morrison’s insightful feedback and her legendary rejection letters, and it was very timely for all of us, as we immerse ourselves in the very techniques that can help us write in a more embodied way.

Just a few more words about embodied writing before we tackle this week’s reading and exercise.

In her article "Embodied Writing: A Tool for Teaching and Learning in Dance," dance theorist Betsy Cooper defines embodied writing as:

… vividly descriptive writing inclusive of an array of sensory mechanisms such that a kinesthetic and visceral experience unfolds during the act of writing and a sympathetic response ensues for the readers.

And psychologist Rosemarie Anderson describes embodied writing this way:

Embodied writing seeks to reveal the lived experience of the body by portraying in words the finely textured experience of the body and evoking sympathetic resonance in readers. Introduced into the research endeavor in an effort to describe human experience—and especially transpersonal experiences—more closely to how they are truly lived, embodied writing is itself an act of embodiment, entwining in words our senses with the senses of the world.

That is so beautiful, Anderson’s idea of “entwining our senses with the senses of the world.”

With this in mind, I want to ask you a new question:

Have you recently brought your full attention to the middle space between your body and the world, that electrified space between what is you and what is not you?

Awareness of this middle space—the distance between ourselves and the world, that liminal space that thrums no matter how close up to the world we get, no matter how pressed against the world we are—is central to embodied writing.

Let’s bring our awareness there this week, as we enter into our next embodied exercise.

Week Two Writing Exercise: Body, My House, My Horse, My Hound

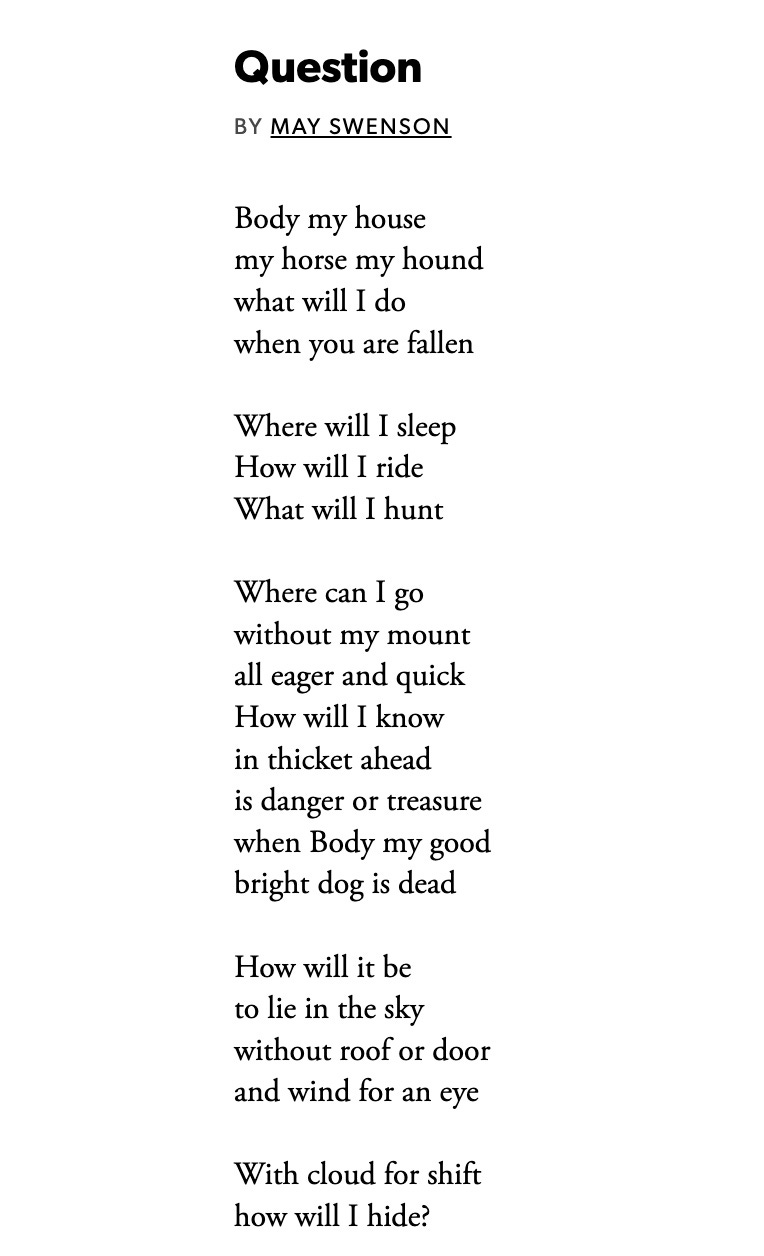

We’ll begin with this incredible poem by May Swenson, which so inventively captures one way of thinking about the experience of living in a body. If we were in a room together, I would read this poem out loud to you. And those of you who listen to

’s audio meditation this week will hear this poem read aloud.But, even still, no matter where else you do or don’t listen to this poem later, please do read it out loud to yourself now (or as soon as you are somewhere that you can read out loud to yourself). I want you to feel the words in your mouth, their shapes and edges on your own tongue, as you ponder the questions Swenson asks here:

Such a strange and marvelous poem.

I dearly love the line about when “Body, my good bright dog is dead.” The externalization of the body here as a “good bright dog” makes me feel the idea of its death in an entirely different way. It reminds me of what some of us did in our thread last week, where we externalized our body as a distant aunt, etc.

And I love the rhythm Swenson creates with her words and lines, and the way I can feel this rhythm in my own body when I read the poem out loud.

What else is happening in this poem?

Well, how about the use of questions? And the interesting repetition of threes in relation to the body as house, horse, hound and the way those three ideas echo repeatedly in the lines that follow, always in that order.

Also this: the incredible idea of hiding behind a cloud as “shift.”

What else do you hear in this poem?

And what do you feel in the poem? Anything? If so, where do you feel it? Can you help me to extend this close reading of the poem in our comments this week? Questions are welcome! Questions are a crucial part of close reading.

To note, I do not find this poem especially visceral. For me, “Question” is a poem written about the body more than through the body. What do you think? And to emphasize, it’s not that the former is good or the latter is bad. They’re just different, and I like to try to name what I see—especially when we ourselves are attempting to write in an embodied way right now.

So, again, what do you think? Is “Question” very sensory, or not so sensory?

I should say, I chose this poem not because it’s especially sensory in my estimation, but because it asks us to consider our body as our house, as our home. So, as we bring our attention to the root chakra this week, we will invite ourselves to recall a moment of deep comfort and “at homeness” in our body.

Below, you will find this week’s root chakra meditation, the accompanying yin yoga pose, our structured embodied writing exercise, plus Billie’s link to the supporting materials, which now includes music to support your writing.

We can’t wait to see you in the comments!