The Dream That Wasn’t: On Letting Go, Becoming, and the Quiet Joy of Making

Lit Salon on the strange holiness of plans that collapse and don't come back

We don’t always know we’re carrying a dream until we’re asked to put it down.

Sometimes the dream is shaped like a marriage. Mine was. A life-long marriage into which I could pour myself for years and then decades. I was twenty-one. Did I even know what a marriage was, let alone a long marriage?

I imagined—though I didn’t even know I was imagining—that marriage meant the same two hands reaching for the same pot of coffee for decades. The same two hands reaching for each other.

I didn’t know that hands could stop recognizing each other’s textures and contours, or their own.

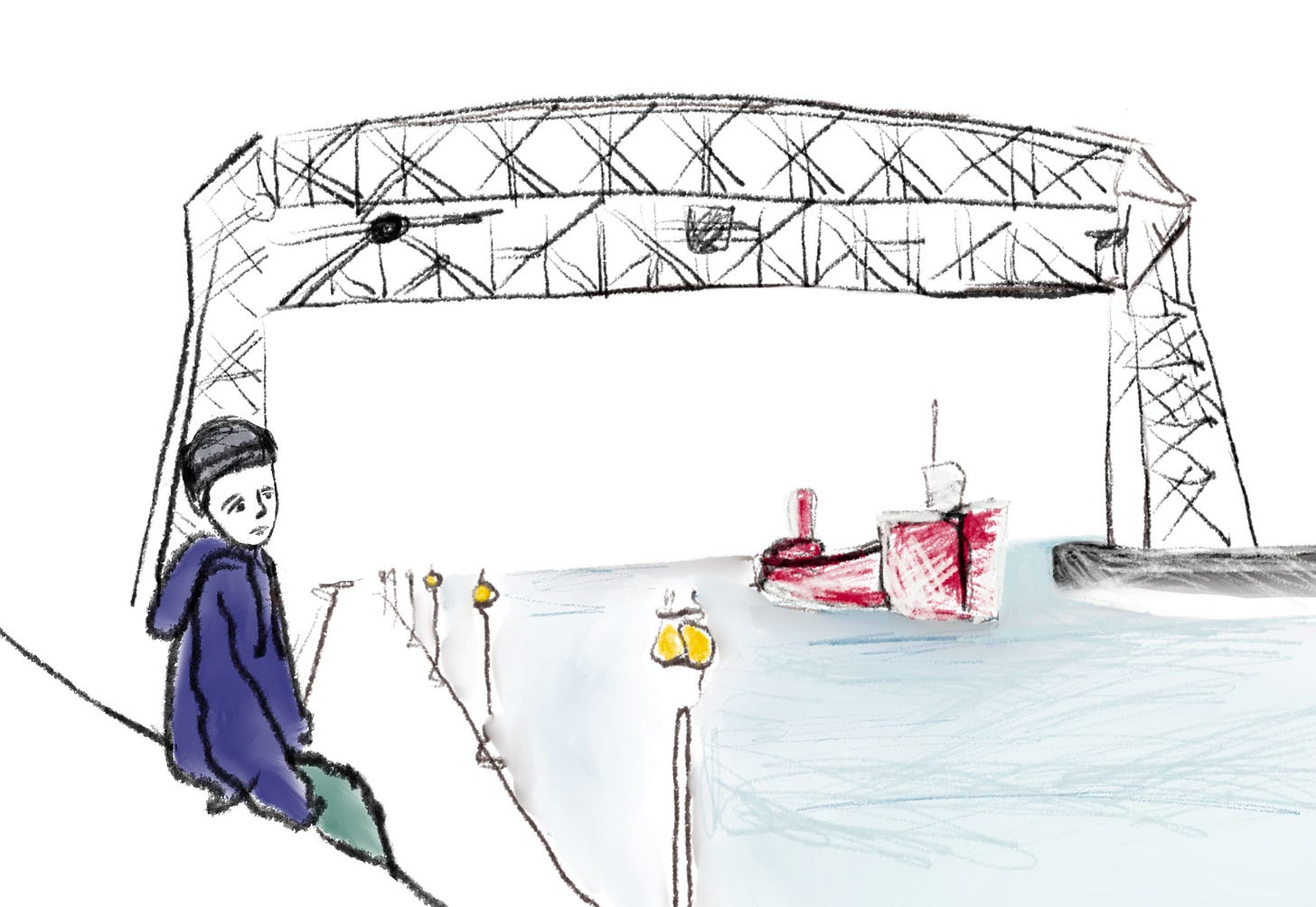

I certainly didn’t understand that marriage is a house built slowly underwater. The furniture shifts. The windows bow. Some rooms stay dry. Others fill with silence, dream-silted and blue.

By the time my first marriage ended—swept away in a storm so fierce and painful that my children and I still unearth its debris even now, twenty-five years later—I was ready to let it go. I was ready to let it go. I was ready to let it go.

I didn’t feel I had a choice. It was already gone.

But that doesn’t mean it didn’t break my heart.

For years, I would weep quietly whenever I saw young couples with children out in restaurants or stores. Surely those parents wouldn’t throw it all overboard. Surely those parents wouldn’t dismantle their children’s boat while still at sea.

But I wasn’t weeping with regret, because I didn’t want my marriage back. I was weeping instead with sorrow for the loss of a future I had once believed in deeply, and a future I had once wanted with all my heart.

We have other dreams, too. Sometimes shaped like a child, still calling from the other room, still wanting our advice. Or shaped like a body that doesn’t ache, or a career that follows a clean arc, or the simple belief that if we just try hard enough, things will go the way we imagined.

But they don’t. A child can become stranger. The body betrays. The story goes off script.

There is a strange holiness in the moment we realize the plan is not coming back. At first it feels like death. Because it is a death. When my marriage ended, I felt, in fact, that a part of me had died. But these moments of finality and release contain something else, too—a widening. A softening. A surrendering into the truth that we cannot require things to be fair or recognizable. That we can love our own life even in the brokenness.

This kind of love—for the unformed, the unraveling, the uncertain—is a different species than what we’re taught to seek. It’s a love that doesn’t offer closure, or even believe in it, really. A love that resists clarity. What this love does give us is open space and possibility. Not the kind of space that detaches us from need or yearning—to the contrary. The kind of space that heightens need and yearning for discovery.

And maybe that’s what letting go of a dream really is: making space, not just for something else to come, but for something truer to surface.

In creative life, this moment of letting go is both terrifying and necessary. Every artist begins with some idea of what the work is supposed to be. But the real work begins when we loosen our grip. When we stop forcing the poem to behave. When we let the essay go sideways. When we follow the wrong character into the wrong forest and discover, halfway through, it was the right story after all.

What if the poem, the essay, the story were never the point? What if the poem, the essay, the story are only artifacts, only the dried husks of something feral and uncontainable, something elemental and alive and sacred, which is our own creativity? What if creativity—the ability to make or otherwise bring into existence something new—was always and will always be the point?

And what if the same could be said of life? That the point is not to get anywhere or even go anywhere, but simply to move curiously and honestly and to allow ourselves to be changed by the process?

In my experience, letting go doesn’t mean we stop wanting. It simply means we want differently. Less for outcome, more for alignment. Less for control, more for connection. We begin to want what’s real, even if it’s smaller than what we pictured. Even if it arrives late, in a different form, or not at all.

A woman loses her marriage, but finds a life into which she can gradually unclench and unfurl, where she can be seen for her whole self. A mother releases her need to be understood, and finds a new peace in tending her own garden. A writer lets go of publishing “the book” and starts writing into that void starts writing away from the known world and into the absolute nothingness of what has never yet been, and in so doing finds a breathtaking level of truth and aliveness, not just on the page, but in herself?

And no, I’m not suggesting that you leave your marriage or give up on your estranged child or shove your novel manuscript in a drawer. When I coach writers one on one, this question sometimes arises, and I generally find that a writer can find her own way to the answer by engaging wholly with the questions with a spirit of radical self-honesty (and that, radical self-honesty, is one of the most powerful tools I know for creating and sustaining a thriving creative life). It is sometimes best to let one project go in order to make space for another, but it’s also true that we sometimes abandon things out of fear of finishing or a disorienting sense of not knowing how to finish. Only we can know the difference. I’m only saying here that sometimes in life, and maybe more often than is easy for us, we reach a threshold where letting go is the only thing we can do.

And through this letting go, we change.

We grow quieter. We grow stranger. We stop asking the work to save us and start letting it keep us company.

Maybe becoming the fullest version of ourselves has never been about accomplishing more or acquiring anything, but rather about shedding what was never really ours to keep. The borrowed dreams. The inherited scripts. The old hungers that no longer fit. The breath you don’t know you’re holding until you finally exhale.

“We must be willing to let go of the life we planned,” wrote Joseph Campbell, “so as to have the life that is waiting for us.”

To have the life that is waiting for us, we have to not only show up for it but also be awake enough to see it. Because it might not be dazzling or even obvious. It may not even be legible from the outside. But it can be real. It can be ours. And inside it, there will be beauty and sharpness and sudden moments of ecstasy and terror.

It’s exactly the same with our creative work. We must be willing to let go of the poem, essay, or story we planned in order to write the one that is waiting for us. And then we must shed the husk of it and grieve its imperfections in order to start again.

Love,

Jeannine

PS Letting go isn’t easy for us. It’s a continual practice. Here’s a short, strange writing exercise designed to work quietly but powerfully on the psyche:

Writing Exercise: “The Room That Isn’t Anymore”