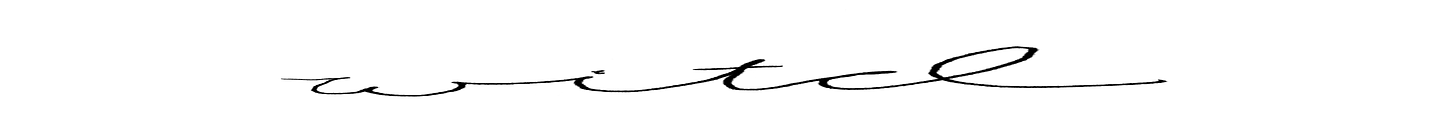

The Shapeless Hour

Lit Salon on what to do when a sentence won’t hold. A self won’t hold. The structure you built, patiently, exquisitely, won’t carry weight. You touch it and it buckles. What now?

First I want to thank those of you who reached out over the weekend about the tragic political assassinations in Minneapolis. We appreciate your love and thoughtfulness, always. It speaks to the kindness and genuine compassion of this community, and I am grateful for all of you.

I also want to invite you again to check out the Friendship thread from last week, if you haven’t already. Writing in the Dark members are reaching out on that thread to form connections, both locally in person and online, and it’s really a lovely thing. And if you posted on thread and haven’t connected with anyone yet, please don’t worry. Algorithms and open rates often keep us from seeing each other, but that doesn’t mean connections won’t happen. We’ll do these Friendship threads maybe once a season to keep the energy going.

This is a time when we offer each other support without measuring or counting, and give each other grace worrying if its due.

Because this is a time when so many things are hard—we need to go easy on each other.

I’m still hearing from so many people who are collapsing under the weight of the world right now. People suffering with depression and anxiety. People grinding their teeth until their jaws stick shut. People losing their appetites or the opposite. Or drinking too much or isolating or simply losing the ability to find pleasure and joy in the activities of daily living.

Especially, I am hearing from people struggling to create right now.

And I think the best we can do for creative paralysis from the unrelenting tragedies and violent injustices all around us is to be gentle.

Just try to be gentle.

Really, it’s the same advice we have to give ourselves during any period of creative paralysis, no matter what the cause—if any. Because sometimes we don’t know the cause, and that can be even scarier.

But the truth is that we all face seasons in our lives when form disintegrates. A sentence won’t hold. A self won’t hold. The structure you built, patiently, exquisitely, won’t carry weight. You touch it and it buckles.

What now?

We live in a culture hungry for wholeness. The endless Insta reels from Insta therapists show me that every day (I’m not saying the reels aren’t any good—some of them are). But wholeness isn’t always not symmetry. For me, it’s never been symmetry. It’s not a flawless bowl or a resolved life. I wasted a lot of time hustling toward that distant horizon of “resolved” before I realized it was a mirage. Wholeness, at least for me, is an ecology of ruins and sprouts, a combination of creative compost and raw drafts.

Sometimes we have to unwrite ourselves.

Brazilian novelist Clarice Lispector once said, “I only achieve simplicity with enormous effort.” She knew: clarity is not where we begin—it’s what we wrestle toward, often with inordinate sweating and panting. And in the course of that wrestling, breaking is not always a setback or a detour. Sometimes it’s the honest beginning of craft.

This is because a certain kind of intelligence only arrives when structure fails. Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han writes, “The crisis of form leads to a deep fatigue, but also a readiness for the formless.” And it is often in that shapeless hour that something original stirs. Rarely is it the shape we planned. It’s the shape that emerges when we stop insisting.

For the writer, rupture is revelation. You lose the map and begin to draw a new one, not from theory, but from instinct. What if the sentence doesn’t lead you forward but pulls you apart? It’s okay to let the rhythm collapse. Let the image split. Let the voice flicker strange.

Let the silence come.

This is not defeat, failure, or even regression. It’s a first step toward the slow alchemy of reconstitution. First must come the silence that exposes the edge. And the edge can be a refusal of false coherence.

The psychoanalyst Marion Milner, herself a kind of covert poet, wrote:

I began to guess that my self’s need was for an equilibrium, for sun, but not too much, for rain, but not always… So I began to have an idea of my life, not as the slow shaping of achievement to fit my preconceived purposes, but as the gradual discovery and growth of a purpose which I did not know.

And so, when we’re silent, we listen for the faint and distant chimes of what was and what might be. When we write, we write toward the possibility of dissolution and reconstitution, not away from it. Revision is a species of forgiveness. Of our earlier selves. Of the idea that we ever had it right the first time.

Donald Winnicott, whose work on the true and false self remains foundational, said:

It is a joy to be hidden and a disaster not to be found.

Winnicott described how the false self survives by pleasing others, while the true self emerges through creative expression and spontaneity. Writing is one place where we are found again. Where we find ourselves. Even in the silent spaces between words. Even when our words lie fallow.

In Transformative Learning Theory, Jack Mezirow identified the “disorienting dilemma”—a rupture of belief or narrative that forces a reassessment of identity—as the beginning of deep growth. For writers, these dilemmas are the generative cracks in voice, the burnt draft, the sudden and extended silences. None of these are evidence of failure. They are the seeds of transformation.

I’m sure some of you are familiar with internal family systems therapy, a method founded by Richard Schwartz, who said, “The Self is in everyone. It can’t be damaged. It knows how to heal.”

The world is on fire, and we don’t know if, how, or when it will be fixed. Meanwhile, we ourselves are never “fixed” either. The work is never “done.” Completion is a myth; but coherence—that is earned, and only through splinter and splice.

Let yourself rupture.

Then write the form that can hold what you’ve become. If you feel like writing, there’s an exercise for you after the paywall. It’s another weird one. I hope you like it if you try it.

Love,

Jeannine

Related Essays

The Importance of Teeth in the Art of Revision

Zero Waste Writing, Or How to Finally Finish A Thing

Finish Better: The Transformative Art of Finishing Things

Writing Exercise: “The Moment It Broke”

Part I: The Fracture