The Uncommon Light of Memory (Pause, Reprieve, Exhale)

Essay in 12 Steps | SIX | the attentive writer... will find that there is, rippling on the edges of a daydream, the unfolding of the perfect solution ~Andrea B. O'Connor

Oh, the irresistible nostalgia of fall. It’s 63 degrees and cloudy this morning in Minneapolis—but even over the holiday weekend, while temps hovered near 100, the dream of autumn thrummed just under the heat. And last night on a walk around the neighborhood with my husband and Billie, Z cruising ahead on his balance bike, we picked a ripe pear from our neighbor’s tree (many more scattered on the sidewalk and boulevard) and dodged acorns falling from above and rolling under our feet, careful for the way they kept “slipping us,” as Z said. We noticed the first leaves turning over head, and the light fading away faster and faster all around us.

My children tell me I have a knack for nostalgia. And melancholy. “You can make anything a little sad,” they say. And they’re right, in part—but as they’ve grown up, they’ve also come to understand the concept of happiness inside sadness, the complexity of emotion that lives in all deeply noticed things. I know this way of seeing the droplet of sad even inside the helium balloon of happy comes in part from my childhood—but it also comes from being a writer. From paying close attention. From learning to see beyond what I think I know.

Also, from learning to cast the “uncommon light of memory” (as Paul Matthews describes it) on the people, places, and things in my life. Matthews describes this light in his creative writing sourcebook, Sing Me The Creation:

A remembered image often has a special light around it, more charged with feeling than the impressions that come to us “in the light of common day.”

This special light is part of what makes memoir so magical. It is part of what makes Z stop in his tracks and plunk down on the kitchen floor, eyes wide and mouth ajar, to listen to stories of before. It is what makes him, and all of us, want more.

But, in every creative endeavor, there comes a point where we feel challenged to continue. We feel fatigued. We may even begin to resent or hate the thing we are trying to create. It’s a sensation most of us have encountered. I have experienced it vividly myself, time and again, and I have coached countless writers through it. There is a reason we refer to the “messy middle.” So, at week six of our twelve-week essay challenge, I am guessing many of you may be flailing here and there (or everywhere).

The constricted instructions might be making you restless. Or itchy. Or irritable. Your topic may be flummoxing you to the point where you’re second guessing yourself or feeling bored by it. The sum total of these frustrations might be making you want to do anything other than write this stupid essay. This moment is sometimes referred to as “writers block” or creative resistance. But I prefer to think of it as a simmering phase. Unexpectedly I found an old article in “Nurse, Author, and Editor” that describes this phase perfectly:

“Simmering” is signaled by an intense compulsion to do whatever task the writer usually avoids most vigorously. Deferred spring cleaning and hand-waxing the family car come immediately to mind, as do sorting through drawers that have languished for months or tackling the stack of ironing that threatens to topple at any moment. For outdoor people, weeding a neglected garden or clearing out the garage become essential tasks that must be accomplished immediately.

It seems that anything and everything is competing for the writer's attention, but a careful examination of these compulsions reveals their commonality: all involve repetitive, physical labor that is relatively (but not entirely) mindless. A certain degree of attention to the task is called for, but the mind is free to wander while the hands work through the job. During this simmering, creative ideas often surface.

If this rings true to you, know you are not alone. It’s all part of the process. The article goes on to advise:

Now a normal person would simply despair, and the writer's usual response is an audible groan and a stoic effort to push off the compulsion and get back to the work of writing. But the attentive writer who has given in to the urge to clean or iron or weed will find that there is, rippling on the edges of a daydream, the unfolding of the perfect solution to the work in progress.

In honor of this wise advice, we’re going to, here at the midpoint, honor our hard work so far and set our essays down for a moment—let them simmer in the background while we revel in the beauty of language itself. While we bask in nostalgia. While we continue our art of noticing. We are going to dive into the uncommon light of memory and emerge from those fresh waters enlivened and more able to press on.

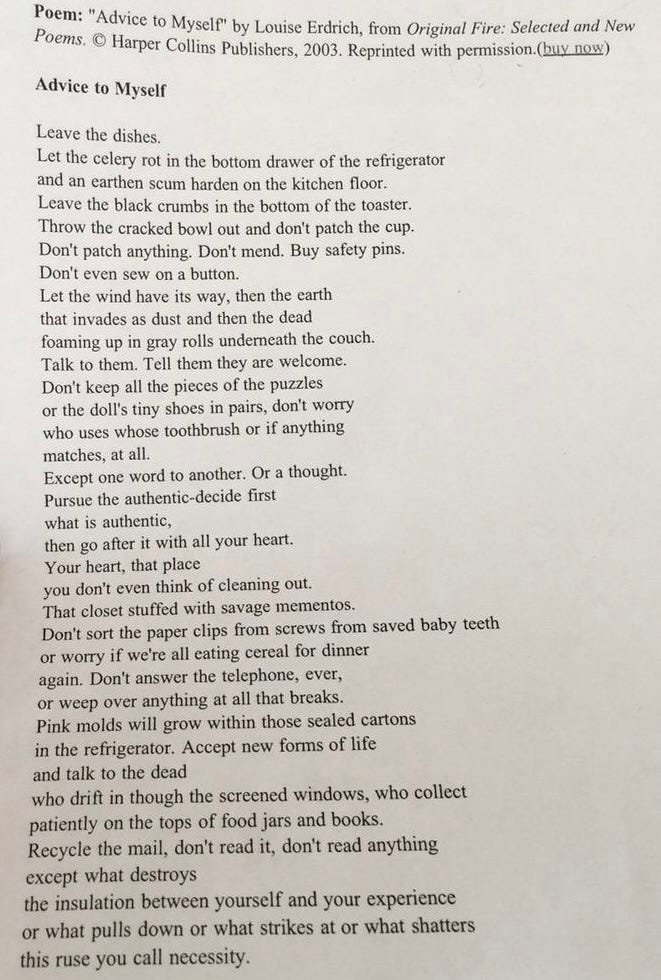

Don’t worry—I’m not abandoning you in this. To the contrary, I’ll guide you through a low-stakes exercise in “simmering” in this week’s formal step work and prompt (which is truly one of my favorite prompts to teach). But first, I have one more sliver of advice for you from one of the most beautiful writers or humans out there “doing language,” Louise Erdrich, in her poem “Advice to Myself”:

My god, I love Louise Erdrich so much.

And now, in honor of my wish for you to revel in the contents of “your heart, that place you don’t even think of cleaning out,” I have a treat for you. You have been working so hard. Let’s relax into the “special light” of memory.

This prompt is one of the most successful creative writing prompts I have ever offered while teaching retreats, workshops, and classes, whether on the beach in Ixtapa, the ice house at Stout’s Island, community ed classrooms, my living room, or Lit B in the basement of Stillwater Prison. Across settings, demographics, and writing backgrounds (or lack thereof), this prompt tends to yield surprising, beautiful, strange, and striking results. Which is why we need it now, in this moment, so you can fall back in love with language for its own sake—and maybe even celebrate the sound of your own voice.