Each scene takes us into a crucial moment ... and should engage both our emotions and our minds by creating real-time momentum or action. ~Jordan Rosenfeld

Week Three | Art of the Scene: Staying In The Story Even When You Leave Narrative Time

Upcoming live events for paid members (all on Zoom):

Nov 25 1-2pm CT Silent Write-In

Dec 13 12-1:30pm CT Open-Mic Salon

Dec 16 1-2pm CT Silent Write-In

You can upgrade here anytime to write with us in our safe, light-filled community.

Last night was the last class session of my Advanced Fiction class at Moose Lake prison, where we have been focusing specifically on scenes.

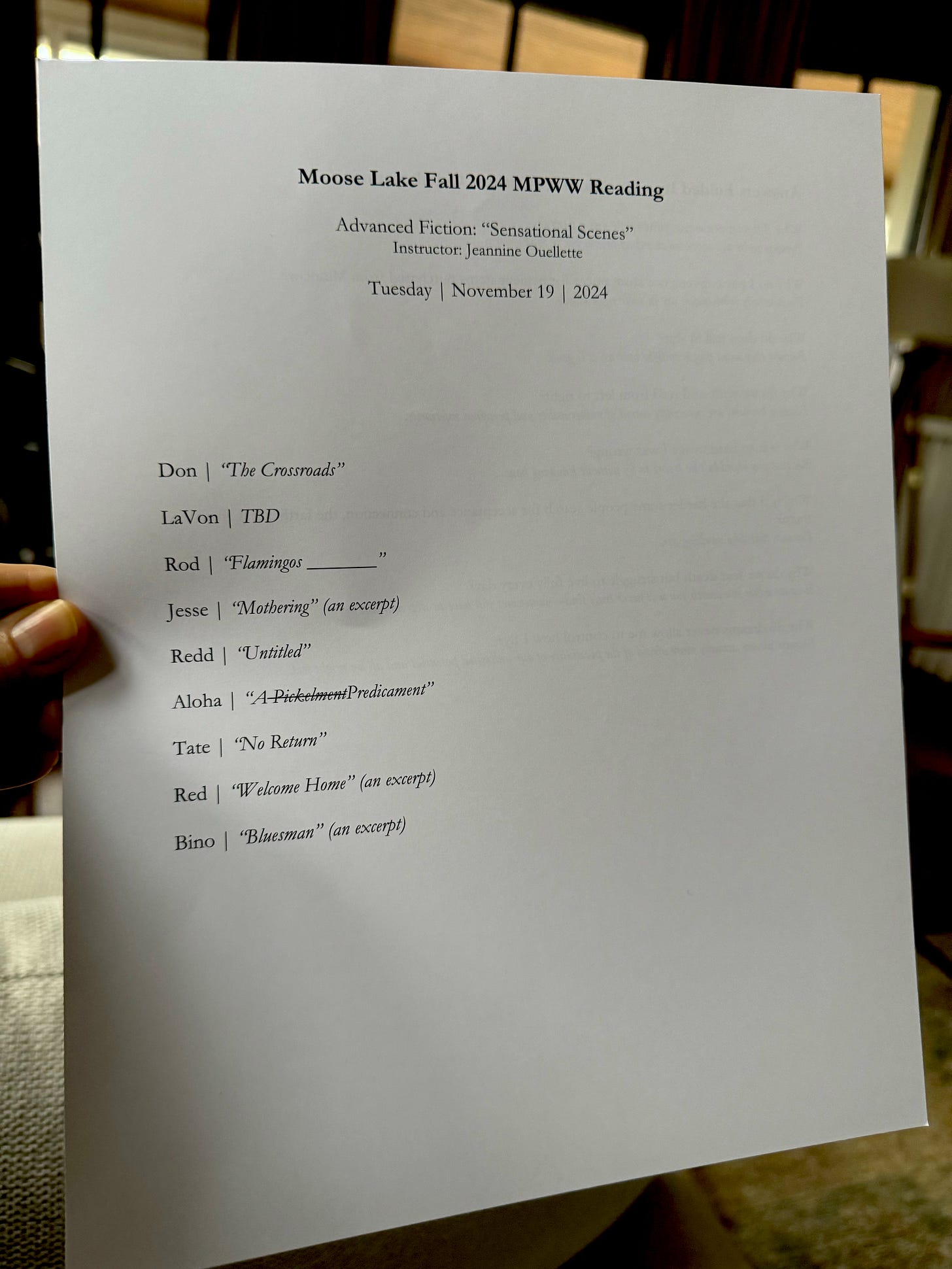

To celebrate our last class, we held a reading. My husband went to Kinko’s to print the programs I made, which turned out beautifully. I also wrote up brief intros for each writer, in order to share a few insights about them as artists, so that the audience could contextualize their work a bit as they listened.

Oh, I should have said, this is special for us to have an audience—it’s difficult to arrange in the prison, but we had one other Minnesota Prison Writing faculty member make the two-hour drive out to Moose Lake, and, in addition, each of my students was allowed to invite a friend (from the prison population).

The readings were powerful, funny, captivating, and evocative, and it was incredible to celebrate the incredible work my students have done over the past twelve weeks.

It was emotional.

My Moose Lake class has been illuminating for me—these months of immersing myself in the shape and sound of scenes, pressing into the edges of what differentiates a scene from other building blocks of writing. We’ve been using an assigned book for this class—Jordan Rosenfeld’s Make A Scene—and it’s been a helpful guide.

Rosenfeld has a second scene book, too, which I also have, called Deep Scenes. She cowrote this one with Martha Alderson. Part of the reason these books are useful is because they are very explicit in the way they define and instruct, making the content very actionable. So much so, in fact, that one of today’s craft readings is an excerpt from Deep Scenes.1 The full excerpt is linked in the footnotes, but here’s an example from it that demonstrates what I mean about the explicitness of the instruction:

The Difference Between Scene and Summary

Not everyone understands the difference between scene and summary, so let us provide a clear distinction. Summary explains something to the reader. It offers information, ranging from long-winded histories of the town your character lives in to pat descriptions or rambling explanations for a character’s behavior. Summary doesn’t engage the senses, and it rarely involves moment-by-moment action.

Examples of summary include:

“It was a beautiful day.”

“She felt happy for the first time in months.”

“She didn’t trust men because her father had been the one to leave her all alone in the boat that night, when she almost drowned, and she now also had a terrible fear of water.”

By the way—those who’ve been writing in the dark with me for some time now might notice that what Rosenfeld and Alderson flag as summary also sounds a great deal like interiority, right? Remember that—summary and interiority have great overlap and this is why excessive interiority can have such a dulling effect on our work.

Anyway, the authors go on to outline several situations in which summary is useful—which is also important because, of course, we will need summary to tell our stories! But the whole purpose of actively studying scene and working our way through a scene intensive like this is to practice the art of writing that is … not summary, whether we’re writing fiction, or, as Lauren Kessler2 explained last week, doing the very same scene-building in nonfiction—except, through the lens of reporting.

One of the things that many of you commented on last week, in relation to the Ann Tyler scene we read, was how little summary or interiority it included. Almost none, in fact. Which is a big part of why I chose that particular scene—to show, if nothing else, that such exterior writing is not only possible, but also powerful.

Also, to show that we can write a block of text that includes one or more characters (and yes, that character can be us) and in which something happens in real time—something happens at essentially the same pace in which we ourselves move through time. Or, put another way, we can write a scene in which narrative time and real time are essentially equal.

You know from Week One and Week Two of this intensive that I believe an awareness of time is our best friend when it comes to scene writing (and an incredibly powerful asset in all of our writing, truly). Specific to scene, time awareness is crucial because the easiest way to truly distinguish whether you are in scene or summary is to check whether the words on the page are located in a specific time and place and moving through a specific span of time at a discernible pace.

By Rosenlfeld and Alderson’s definition, that would have to be moving through a span of time that is within the main narrative timeframe of the story—in other words, not summary or backfill. But, to my mind, a scene might also take place as a flashback. So, here is a good time to mention that although flashback and backfill are similar and can have overlap, I actually use these terms distinctly to mean slightly different things.

So, backfill might sound like:

Back then, we used to walk to and from school every day, no matter the weather, even when the snow came down in fistfuls, and sometimes, we’d take detours into the cavern of Lincoln Park to play…

Whereas a flashback would sound like:

One morning when I was seven, we were walking to school as we always did, and the snow began falling in white fistfuls, heavy and wet, perfect for snowballs, so we detoured into the cavern of Lincoln Park, where we …

It may seem like a subtle distinction, but it’s really not. In the first example, time is continuous—the narrator is reflecting on things that happened repeatedly over a vague and nonspecific period of time. In the second example, time is specific, something is happening in a specific moment, moving through a specific span of time.

Do these types of backing up in time sometimes overlap?

Surely, the do.

Still, I think it helps to label things, even if the labels are insufficient.

As I said earlier, most stories/essays/novels/memoirs do include some flashback material to deepen the narrative for one reason or another. And flashback can be written in scene, not summary—and even backfill can be full of rich, concrete and specific sensory detail that makes us feel as if we are in the story.

But we know that long-winded, summarized backfill that is not grounded in concrete sensory detail can be extremely boring and slow the story down. It’s also true that even very well-written, scene-based flashbacks can, if used indiscriminately, deflate narrative drive.

For all of these reasons and more, we’re going to look this week at the opening of a Sue Miller novel.3 In this novel, Miller demonstrates—not just in the opening, but throughout the entirety of the novel—a brilliant deftness for weaving backstory into the narrative time of the novel. Honestly, she does it with almost surgical precision. She’s so good at it that, if you weren’t watching for it, you might not even notice. Additionally, this novel actually includes an entire chapter of backstory that, despite its long departure from the main narrative timeframe, kept me spellbound.

I guess on reflection, some might even say that the Miller novel on the whole is a braided story with two separate timelines, but I can say that until right this minute, trying to describe the deftness with which she manages time, I have never, not even once, thought of this novel as having a dual timeline. For one thing, it does not alternate time periods chapter by chapter as most of such novels do—not at all. Instead, it (mostly) stays in one narrative timeframe, weaving the backstory in organically, once as a whole chapter, but mostly—and certainly in the opening that we’re looking at this week—within the main narrative timeframe.

Which is exactly what we are going to do next.

I think this will be useful for us, since we’re all so prone to adding backfill even when we’re trying not to! We may as well learn to do it well!

Writing Exercise: Staying In The Story Even When You Leave Narrative Time (Or, the Art of Backfill)

Step One

For this week’s exercise, your first job will be to close read the opening to the Sue Miller Novel (and the essay I linked in footnotes if you like to geek out on this stuff with me, but that’s up to you).

By opening scene, I mean at least until the narrator and her daughter leave the post office with the letter and get to the cafe, though you of course can and might want to continue reading until you find out what is in the letter. In fact, the linked sample goes through all of the first chapter and even into Chapter Two, which is the backfill chapter that I mentioned, and you might be interested in having a look at how Miller opens that, too! But for our discussion purposes, we just need to read until they’re having their dinner at the cafe.

However far you read, take your time with the part of the scene that takes us to the cafe. Look very closely at how it works.

Here are some questions to consider for our close read (answer as many or few as you like):

In the opening, can you separate the backfill from the main, narrative-time story, and see how Miller weaves it in?

How much real time passes in this scene, from the post office to the cafe?

What happens in the scene? (Answers to this will vary based on how far you read, and that’s fine—we’re just trying to identify the actual events on the page vs. the backfill.)

This is a much more interior scene than the Ann Tyler opening we looked at last week. Do you see interiority in this scene outside of the backfill? If so, how well does it work for you (i.e., how engaging is it), and why?

Is there any suspense? If so, where does it come from?

The pacing is obviously much slower than the Tyler novel. Does the story still have sufficient narrative drive for you? That is, does it keep you engaged and reading, despite the slower pace? If so, why do you think that is?

Anything else to share?