“My hands wanted to touch your hands, because we had hands.” — Frank Bidart

Week TWELVE | For the Joy & the Sorrow | Tenderness Is In The Hands

I can’t believe today is the last post of what has been an epic 12-week intensive: For the Joy & the Sorrow, inspired by

’s incredible The Book of Delights. What a joy and honor it has been to burrow under the skin of this work with all of you, and to write with you, and to read your beautiful, surprising, jagged, strange, jarring, soothing words.I predict many of the snippets you’ve written since January will find their way into your works in progress and/or become new works of their own. I can already see that happening.

As you know, we’ll start mid-April with our Writing Toward Pleasure intensive, which I wrote about in detail yesterday as part of the re-cap of my AWP panel on writing real sex (here, if you missed it: Writing the Everyday Erotic | How & Why). Other recent posts related to the upcoming pleasure intensive are: Even in the Dark, We Are Alive, and Is Pleasure Guilty? and Writing Toward Pleasure. And if you’ve never done a WITD intensive, you can check out all past intensives here!

“There was once a very great American surgeon named Halsted. He was married to a nurse. He loved her — immeasurably. One day Halsted noticed that his wife’s hands were chapped and red when she came back from surgery. And so he invented rubber gloves. For her. It is one of the great love stories in medicine. The difference between inspired medicine and uninspired medicine is love.”

— Sarah Ruhl, The Clean House

This week, we’re looking at essayette #10 in the Book of Delights, “Writing by Hand,” an ode to the uniquely and creatively freeing experience of using our hands to write, using our hands to bring forth our ideas and observations and experiences and emotions through ink in a notebook versus typing on a laptop or iPad or whatever.

And I love that we are ending with this essayette—and it was, as I bet you can imagine, very difficult to select one to end on! The pressure!

But this one feels just right, because it brings our attention to our writing in a concrete and specific way, which is right where we want to be, I think, as we conclude this wonderful work. That is to say, we want to be with our writing, we want to be situated fully inside of our writing, we want to be inside of our writing with a heightened awareness of who we are here, what we do here, how we do it, and why.

Writing by hand is a significantly different bodily experience than typing (which, to be fair, still usually requires the use of our hands unless we are using voice adapted technology, but, for now, we’re comparing typing and writing by hand).

“I wondered what that was like, to hold someone’s hand. I bet you could sometimes find all of the mysteries of the universe in someone’s hand.”

— Benjamin Alire Saenz, Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe

Most of us have heard about the growing body of research showing how writing by hand boosts memory, creativity, brain connectivity, and even cognitive function. But there’s an aspect of that research you might not have thought about yet, and that I want to bring to our attention—it’s on how muscle movement builds memory, and how even the simple act of signing our name by hand versus typing confers benefits.This quote is from Denis Storey writing for Psychology.com:

But what about signing your name makes such a difference over typing it out?

“We have shown that the differences in brain activity are related to the careful forming of the letters when writing by hand while making more use of the senses,” van der Meer explained.

Based on that, using the hand – and fingers – to form letters, the researchers claim that print writing will show similar benefits. Subsequently, simply pushing a key is less stimulating.

Meer pointed out that it’s why kids who’ve learned to read and write on a tablet or laptop struggle to discern between certain letters that can appear alike.

“They literally haven’t felt with their bodies what it feels like to produce those letters,” van der Meer said.

I love love love this idea of what it means to “feel with our bodies” what it means to produce letters … and words, and images, and ideas.

Ross Gay, too, in his essayette “Writing by Hand,” notes the connection between the body and the writing when he says, “To be sure, [writing by computer only] would have less of the actual magic writing is, which comes from our bodies, which we actually think with, quiet as it’s kept.”

What a strange, gorgeous, marvelous sentence—the kind of sentence Gay gives us again and again, which makes us work a little harder, get a little closer up to the words in order to get inside them. He knows this, too, and even celebrates how much more likely he is to create this kind of sentence when he’s writing by hand, because he can allow for it in a way that’s challenging when “word processing.” He says about writing on a computer:

And consequently, some important aspect of my thinking, particularly the breathlessness, the accruing syntax, the not quite articulate pleasure that evades or could give a fuck about the computer’s green corrective lines (how they injure us!) would be chiseled, likely with a semicolon and a propoer predicate, into something correct, and, maybe, dull.

I love this—it’s like Gay giving a nod to himself and to the stubbornly strange and brilliant “accruing syntax” we’ve been celebrating in his work throughout this intensive.

So, as we close read this short, vigorous essayette and write in response to it, I invite you to first do two things:

Find a pen/pencil and notebook/paper

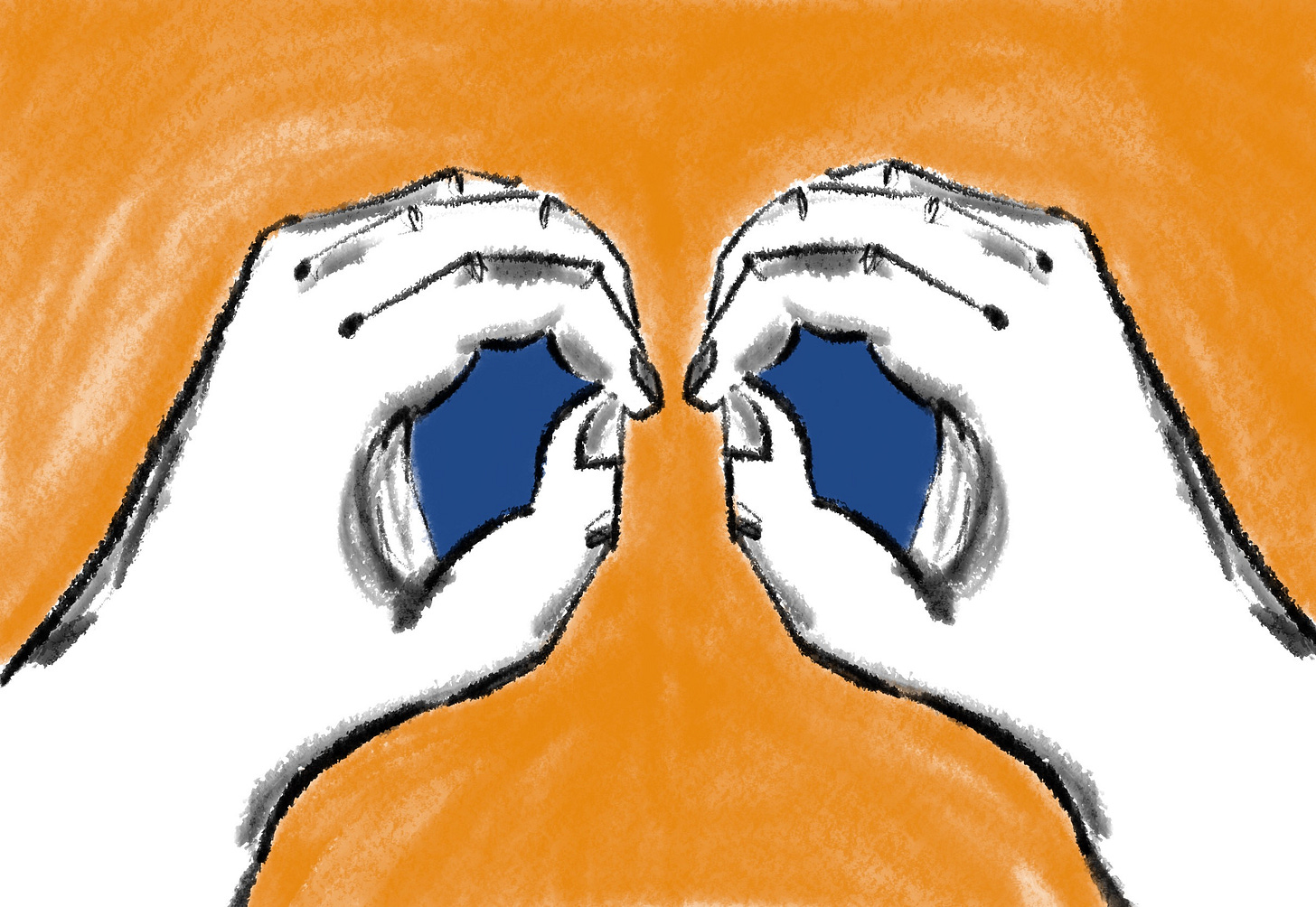

Study your own hands for five minutes. Just hold one hand in the other. Note the texture and sensation of your palms, your wrists, your fingers. You can even try to draw your hand if you like (today’s illustration began with Billie drawing their own hand with pen on paper). But whether you draw or not, take this time to notice and appreciate your own hands. Perhaps consider the following Carolyn Forche quote as you sit with your hands.

“The heart is the toughest part of the body. / Tenderness is in the hands.”

— Carolyn Forché, from “Because One is Always Forgotten”

Now that you’ve taken a few minutes to be with your hands, we are ready to get closer up to Gay’s words and do our own writing in response to “Writing by Hand.” As always, I am excited for your words, and especially now, with strange and inventive exercise with which I hoped to capture some of Gay’s own “not quite articulate pleasure.”