I have lost many things.

When I was a child, we moved almost every year, a kind of restless migration that blurred one home into the next. Each time, small things vanished: books, toys, clothing, shoes. That one record with the “Spanish Flea” song my sister and I used to blast on our toy record player as we danced wildly on our beds. And yes, I had to work to find the name of that song, which I didn’t know then so could not possibly have conjured from a filament of the past that exists only as a feeling-sound in my body, a feeling-sound in a long-lost dim room with two Big Eyes-style “paintings” on the wall and two twin beds with thin cotton chenille-patterned bedspreads. Speaking of which, those paintings, those bedspreads, that record player, those things all disappeared eventually, too.

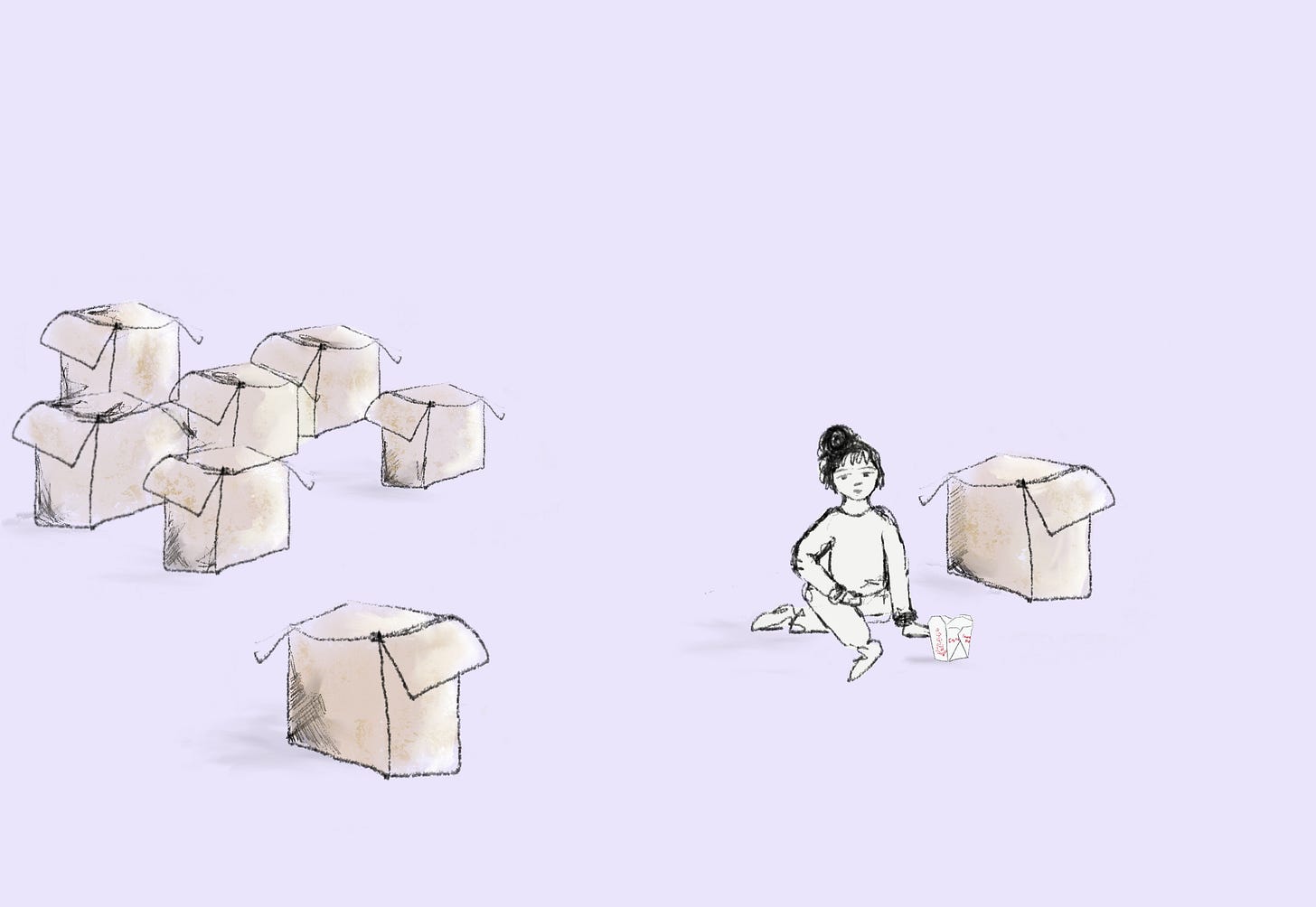

So much packing and unpacking had a dual effect—it taught me that loss is ordinary, the background hum of a human life—but also made me exquisitely sensitive to it. Even now, when I misplace something as inconsequential as a bobby pin, I fret and fret, not because I need it, but because I long to know what happened. Where did it go? How did it slip my grasp?

Mary Oliver once wrote, “To live in this world, you must be able to do three things: to love what is mortal; to hold it against your bones knowing your own life depends on it; and, when the time comes to let it go, to let it go.”1 I’m not always good at that last part. I sometimes hold too long, too tightly.

As a child, I lost homes, schools, teachers, and the imagined futures that once bloomed around each new beginning—the way I thought one place might become the place, that one self might become the self. Instead, my mom lost the last of her homes I lived in, and I lost the version of myself who had never lived in foster care.

Each move left behind a version of me who might have belonged there, who might have grown into something steadier had I not become the new girl once again come September. By the time I was twelve, I had learned to travel light, not because I wanted to, but because I had to.

Twenty-five years ago, at the end of my first marriage, I lost not only the husband, the friend, the marriage itself, and the future I considered already mine and inhabited in a future place that already existed, but also the scaffolding of who I thought I was. I lost my sense of myself as a model mother. My financial security. My willingness to judge others for loving the wrong person at the wrong time in ways that fracture the world around them. Loss has a way of stripping us bare. Rilke said, “The purpose of life is to be defeated by greater and greater things.”2 I have been, and perhaps that is grace—each defeat widening me, hollowing a space inside where compassion might live.

I’ve lost countless pets including several dogs, four cats, one hedgehog, one guinea pig, innumerable fish, at least three hamsters, one lizard, and a parakeet, to name a few. I’ve only lost one job—my university position, dissolved in a sweep of federal research cuts. All the others I’ve left on purpose, which is its own kind of loss. I’ve lost countless keys, a perfectly good Cuisinart, an expensive Le Creuset Dutch oven that was a gift from my former mother-in-law, whom I also lost.

At seventeen I lost my virginity, though not my fear, nor the abject separateness that cloaked me then. Those have taken decades longer to gradually erode, softening under the steady tenderness of my husband’s hands—tenderness that, in the truest intimacy, also carries its own kind of wounding. To be known wholly by another person is to be both opened and undone.

Each loss is both singular and not, because all losses thread into another. The bobby pin glimmers faintly beside the vanished job and the vintage record player, beside the child I once was and the person I once believed I could become.

Pema Chödrön writes that “nothing ever goes away until it has taught us what we need to know.”3 I wonder what my lost things have tried to teach me. Maybe that everything is on loan. Maybe that our task is not to keep but to notice.

When I was ten, I lost my great-aunt Lala. When I was nearly grown, I lost my Nana. Together, those old hens (as they called themselves) loved me in ways I craved but never felt at home. At ten I also lost my stepfather very suddenly, not to death but to disappearance—though I would never say I had had him to begin with—no love, no claim. Only harm. My father, I lost more slowly: first to divorce, then to his second family, and finally to the long ache of distance and disinterest. Maybe the latter was regret in disguise. I’ll never know, now that he’s gone for good. Meanwhile, there are other losses I can hardly name, losses that carried away parts of myself, leaving absences that hum inside me—a constant low-frequency vibration with no known source. Named or not, these empty places count in the arithmetic of loss.

Rumi said, “Don’t grieve. Anything you lose comes round in another form.”4 I want to believe that. I want to believe that what is lost is also transformed—that absence itself might be a rearranged presence. Sometimes I imagine all my lost things gathered in some vast elsewhere: rings and dogs and fathers, schools and selves, each glowing faintly, as if waiting to be recognized.

There are other losses too, less grand but no less real: the friendship I let erode because pride outweighed tenderness; the manuscript draft I overwrote by mistake; the memory I can’t quite recover—something about a swing, a yellow dress, a summer evening—and the ache that rises when I reach for it and find only blur.

Maria Popova writes that “loss is the price of life’s richness, for every gain of being is a loss of becoming.”5 That rings true to me: every version of ourselves that grows must shed a former skin. I’ve lost bitterness, mostly, about my stepfather, about my parents’ failures. Not all of it, but most. And with it, I’ve lost the will to keep stoking that fire. That feels like an earned kind of loss, the kind that makes room for light.

Sometimes, I think loss is the true medium of living. It is the invisible ink behind everything we love. Audre Lorde wrote that “we were never meant to survive,”6 and yet we do, over and over, through a thousand tiny extinctions. Each time we lose something—an object, a certainty, a person—we are rewritten.

So maybe what I’ve learned, after all these years of misplacing things, is that loss is not the opposite of having. It’s the shadow that gives form to what remains. The space that teaches us, over and over, how to see.

Love,

Jeannine

PS An Important Note To Subscribers

Again: My heart is full of gratitude for this community, and every single person here.

Your investment in this community means everything to me, and I am investing, too.

I have several opportunities for writing together in the coming weeks, including a write-in at 2 PM Central tomorrow!

Plus, two great intensives for paid members coming up in December and January, so a great time to give the gift of Writing in the Dark to a friend who might love being here.

It’s also wonderful when you like and share posts and make comments, because as you all know by now, the algorithms. The algorithms.

Thank you so much for being here. I love you a lot.

xo

Upcoming at WITD—Write With Me!

WITD | The COMMONS Write-Ins for paid members (upgrade here to join all COMMONS events on Zoom!)

Wednesday Oct 15 at 2 PM Central

Monday Oct 20 at 10 AM Central

Write Small: A Teeny, Tiny Micro Flash Immersion- our next 6-week WITD craft intensive for paid members starts in November and focuses on micro flash and the challenge and value of writing small.

Essay in 12 Steps: Our first 12-week WITD craft intensive of 2026 for paid members—we’ll reprise the beloved Essay in 12 Steps from start to finish and see what we can make together, one strange step at a time.

Remember, you can always check the full WITD calendar here.

Craft Intensive for Transforming Your Hardest Stories into Beautiful Art (safely and effectively)

Telling Hard Truths - A 3-Hour Craft Intensive on Zoom October 30, 1-4 PM Central. This workshop explores the question, How, though, do we tell hard truths without drowning in them? How do we write what matters most without losing the reader—or ourselves? This is where writing hot cold comes in.

This workshops is registering now and/or you can read more about the concept of writing hot cold here, in the post I wrote recently called The Temperature of Truth.

Oliver, M. (1992). In Blackwater Woods. In American Primitive. Little, Brown and Company.

Rilke, R. M. (1939). Letters to a Young Poet. Translated by M.D. Herter Norton. W.W. Norton & Company.

Chödrön, P. (1997). When Things Fall Apart: Heart Advice for Difficult Times. Shambhala Publications.

Rumi, J. (13th century). Quoted in Barks, C. (Trans.) (1995). The Essential Rumi. HarperCollins.

Popova, M. (2019). Figuring. Pantheon Books.

Lorde, A. (1978). A Litany for Survival. In The Black Unicorn. W.W. Norton & Company.

Thank you for this Jeannine. Another beautiful essay!

My thoughts:

At a certain age, your losses increase at an alarming rate. Mentors, teachers, colleagues, family members, classmates, lovers---all suddenly gone to their just rewards. Dreams, ambitions, wishes, hopes, desires, even memories vanish, never to be seen again.

These losses are replaced by other things. Regrets and desires for forgiveness blossom, for example. These losses are offset, too, by wisdom gained the hard way---by living your life and making mistakes. Often the same damn mistakes multiple times, if you are, like me, a stubborn fool sometimes.

Then one day, without fanfare, a certain peace settles upon you. Uncertainty ceases to matter. Gratitude in things large and small bursts forth like spring flowers. You pass from desperate "doing" to joyful, restful "being." And that one day is worth all the lifetime of losses. The scale of your life is balanced, but likely not as you expected or wished.

If you too have reached that one day, can I have a big, loud "Amen"?

Today would have been my father's 89th birthday. He died at 51 when I was 28. I was already thinking about loss today and your gorgeous essay shines so much light on what were dark thoughts of regret and anger and what was left unsaid.

My father was in the Air Force and we moved every couple of years and sometimes more often. This sentence is still ricocheting around my ribs: "Each move left behind a version of me who might have belonged there, who might have grown into something steadier had I not become the new girl once again come September."

So much love to you, Jeannine. You, and your beautiful words are a harbor of hope in these dark times.