The good piece of writing startles the reader back into Life. The work ... this false life that is even less than the seeming of this lived life, is more than the lived life too. ~ Joy Williams

Story Challenge | Week 10 | Memory is a persuasive force on consciousness, John Mauk says. Narrators use that force while creating an illusion of story horizon. Here's how. (Also, AWP Flash Sale!)

Happenings & Other Stuff

🗓️ Save the date! Our Final Live Salon for Story Challenge is Saturday March 2, 11-Noon CT! We’ll celebrate our hard work with flash readings, a Q & A, and more (Zoom link sent 2 hrs ahead to all founders; manage your subscription options here & let us know you’re coming in the comments (& ask questions if you’ve got ’em!)

✍🏼 Our next seasonal intensive for paid subscribers, The Visceral Self, starts April 3 and is devoted to embodied writing. Get all the info here and here, and please join us!

🎉 AWP Flash Sale: 20% Off New Annual Subs Through Friday (New Subscribers Only)

Hi, hello!

I love the two simple story techniques we’re going to explore this week—memory and horizon. They’re easy and fun, yet do big work to make our stories more real and vivid.

But … before we jump into Week Ten of Story Challenge to explore memory and horizon, I want you to know that I am, just as this post hits your inbox, way up high in the sky en route to AWP in Kansas City.

For those who might not know, AWP is shorthand for the largest, most overwhelming annual writing event of the year in North America—the academic conference of the Association of Writers & Writing Programs. If you are in Kansas City, please find me and say hello!

Either way, if you’re not yet a paid subscriber and want full access to this incredible community of people doing language together (in the most inventive, curious, inspiring ways), take advantage of a 20% discount on our annual subscriptions with our our traditional AWP Flash Sale, good through Friday.

This is for new subscribers only—Substack doesn’t allow existing subscribers to use this coupon to upgrade from weekly to annual for the discount; I’m sorry about that. But to those of you already subscribing, thank you truly, madly, deeply.

You’re making the most beautiful community here, and I’m excited about it every single day. Doing language does move mountains, it turns out.

Meanwhile, a couple of quick AWP thoughts below. (But if you want to skip straight ahead to this week’s musings on story and the structured exercise, just scroll down the bolded header, Horizon and Memory and we’ll get right to it!)

AWP is a giant, convention-center style conference attended by about ten thousand people. It’s overwhelming. But, also, I see many writers I know and love there. Plus, the conference center buzzes with creative energy.

And I experienced a life-changing—or at least life-affirming—epiphany at my first AWP in my home city of Minneapolis in 2015. I was just embarking on my MFA at the age of 45 back then, and the epiphany was the quiet, but powerful understanding that for many aspiring writers, a “successful” writing life is not necessarily glamorous, but is possible.

I wrote about that last summer, in Dear Stuck, who wanted to know why it can be hard to engage with creative work, to finish things and put them out there. And I said, among other things, that it helps to accept our own ordinariness as art-makers:

I discovered, while drifting dazed, confused, and inspired through that sprawling, fluorescent conference, that an “ordinary” writing life was anything but, and that even though most of the these midlist authors and MFA students in that convention center would likely never achieve the acclaim of the keynote speaker or even the slender swath of more famous panelists, they were doing something just as urgent, if not more so, which was to show up for their own “creative power restive and uprising,” and give it “power and time.”1

That, I decided then and there, was the beginning and end of it: whatever else happens—how good our work is, how important it is, how impactful and recognized it becomes—is mostly out of our hands.

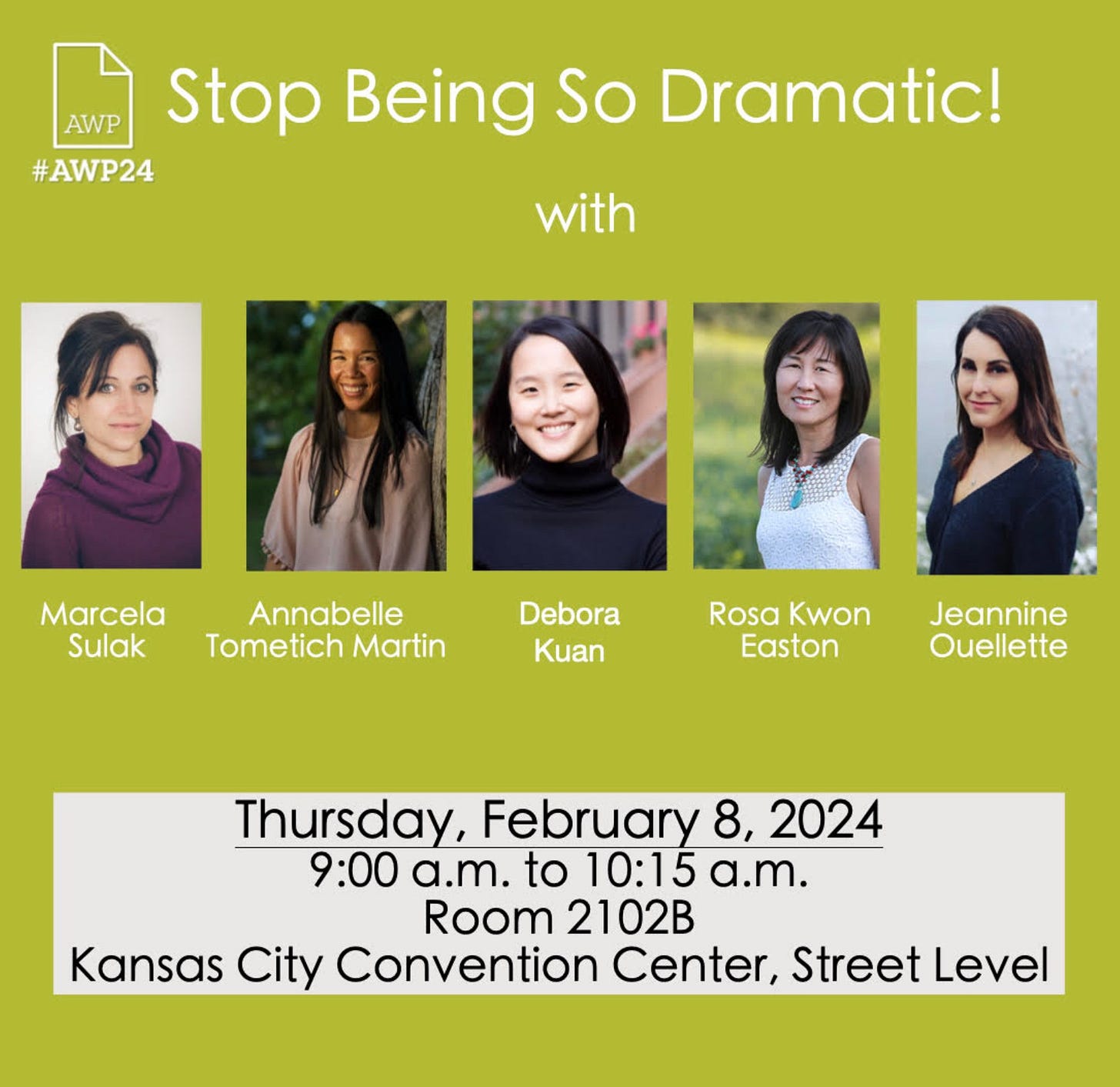

In Kansas City, I’m speaking on a panel called “Stop Being So Dramatic,” focused on how we tell the hardest stories, the ones people are afraid to hear, without overwhelming ourselves or our readers.

From the panel description:

There are some stories so unbelievable, so horrible, or merely awful, but they must be told, for survival. How do we write about the overwhelming without overwhelming the reader? We are five memoirists, poets, and novelists, who write about things others would probably rather not hear about, but we've mastered drama (and dramatic technique), the understatement, humor, the fable, the archetype, third-degree emotion. We will share these techniques that help us develop an audience that asks to hear more.

Marcela Sulak, editor of The Ilanot Review, who organized this panel, also nominated my essay, “The Cost,” for this year’s Best American Essays (winners will be made in April). This is my first BAE nomination—and for an essay that details what writing has cost me, that means even more.

I’ll share some photos and highlights from the conference once my feet are on the ground … and I get my hair colored, which I’m doing as soon as I land, god help me and send luck. Otherwise, if you are in Kansas City, you can find me at the panel or the Split/Lip 10th Anniversary reading. Also, I’m doing an author residency at the Split/Lip table at the book fair on Thursday from 11 AM to noon.

And, again, please consider taking advantage of the flash sale for 20% off annual subscriptions.

Now for Horizon & Memory!

As I said, we’re going to shake it out this week, get our bearings (literally) and try some lighter exercises before we jump headlong into the heavy lifting of aboutness next week. For now, playing with horizon and memory can be a bit of a reprieve, and hopefully a revelation, too.

John Mauk in his Writer’s Digest essay, “Three Things Your Novel’s Narrator Needs to Accomplish” (which we also looked at in Week Eight of Story Challenge, “The Narrator’s Promise,” writes:

Narrators don’t simply say what happened. They create a reality, a world that readers believe, keep on believing, and want to keep believing… [and] make fictive worlds real, which takes a lot of persuasive power.

In Week Eight, with the Narrator’s Promise, we explored Mauk’s assertion that good narrators make us believe they’ll tell us everything they remember, as soon as they remember it. This week, we are going to explore two other essential tasks of a good narrator—memory and horizon—which Mauk describes below:

Memory

Memory is a persuasive force on consciousness—a reflex that keeps convincing us of this reality. Narrators get to use that force…. They establish a detail (the way a family cat limps or the fact that Melissa spilled a full cappuccino in her Toyota Corolla last Tuesday) and then bring that detail back at some later point: there’s Limpy the cat again and that milk has created a serious funk now that it’s a week old. Each time the cat walks through the house, every time that dead milk smell wafts up from the floor, readers … are comforted by what they already know and reminded that they belong here in this world.

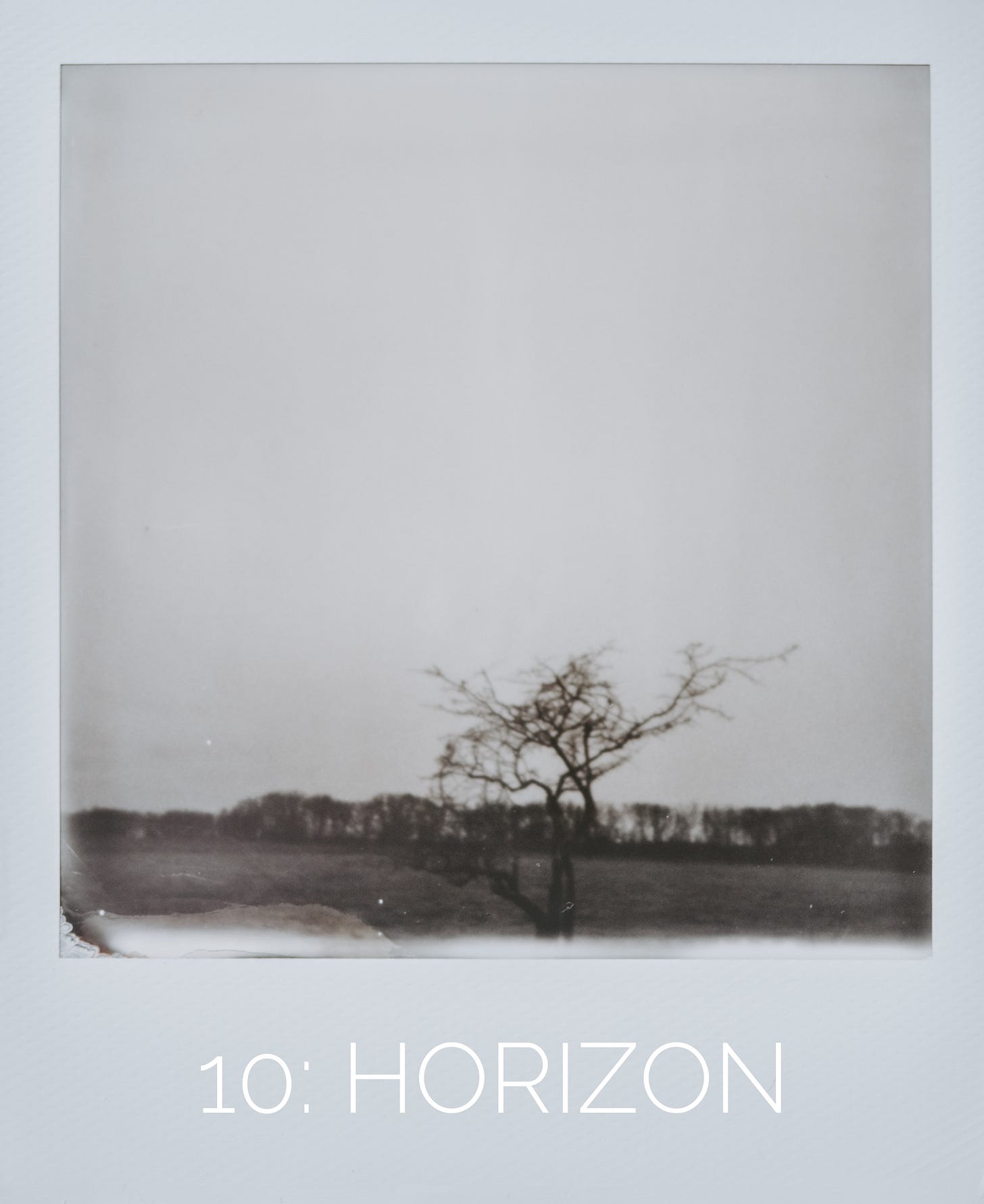

Horizon

Every reality has a place where vision stops, where the walls, mountains, trees, or curvature of the Earth won’t let us see further. The basic feeling of location comes only because we can’t see everything at once… If [readers] are to belong, they need horizon, a way to distinguish here from everywhere else. There are countless ways to make this happen—a small stream of facts that murmurs of faraway business, a finger of smoke, something we see in the distance, anything that lets us know that a factory is churning, that a reactor is reacting. The most stunning and explicit version of this—at least in my mind—is Love in the Time of Cholera. Even the title suggests the up-close and the faraway. In the story, the narrator occasionally reminds us of some distant affairs—national turmoil, sickness, and brutality writ large. And those affairs occasionally haunt the immediate.

As I said, I love both of these simple, doable techniques for the ways they can dramatically strengthen our stories.

In order to help us practice and integrate these concepts and apply them, I’ve crafted three doable exercises you can put to work right away in the story you’re already building or just in some new scenes if you’d rather just treat this as practice. Because anyway, we’re always practicing (or should be).

Please share what you come up with—plus questions and insights!—in the comments. I’ll be there on and off today but also through the rest of the week, reading your stuff and sharing my thoughts and any opportunities I happen to spot.