“Time is a game played beautifully by children.”― Heraclitus, Fragments

Week Five| Art of the Scene: Slowing Down Time

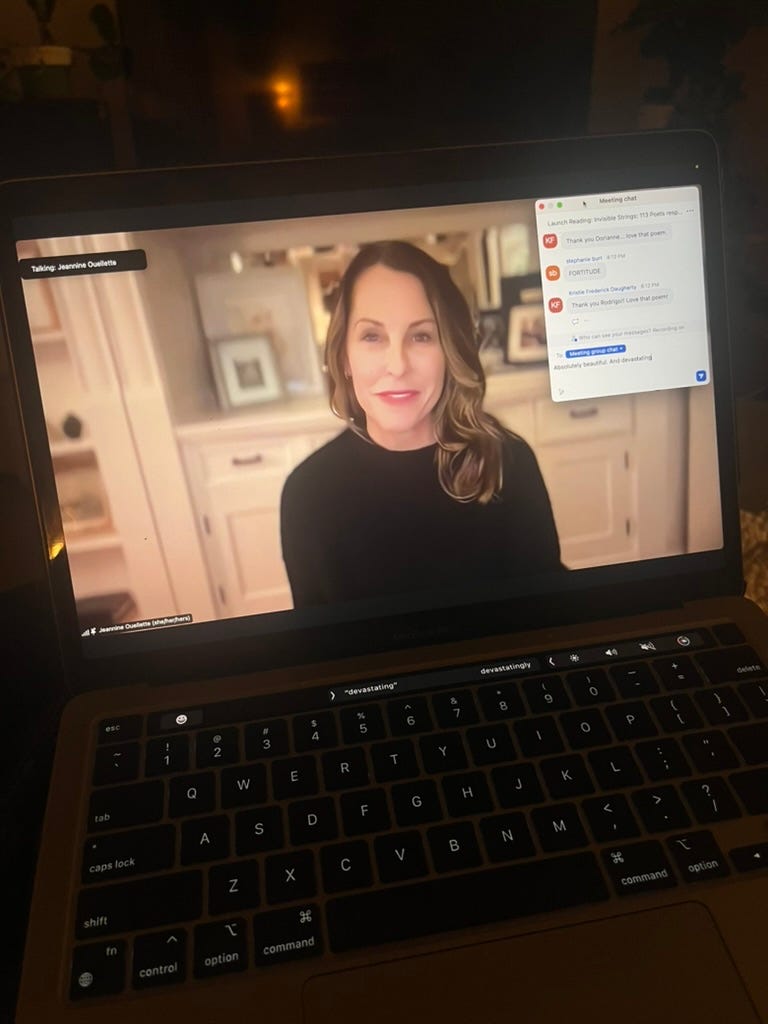

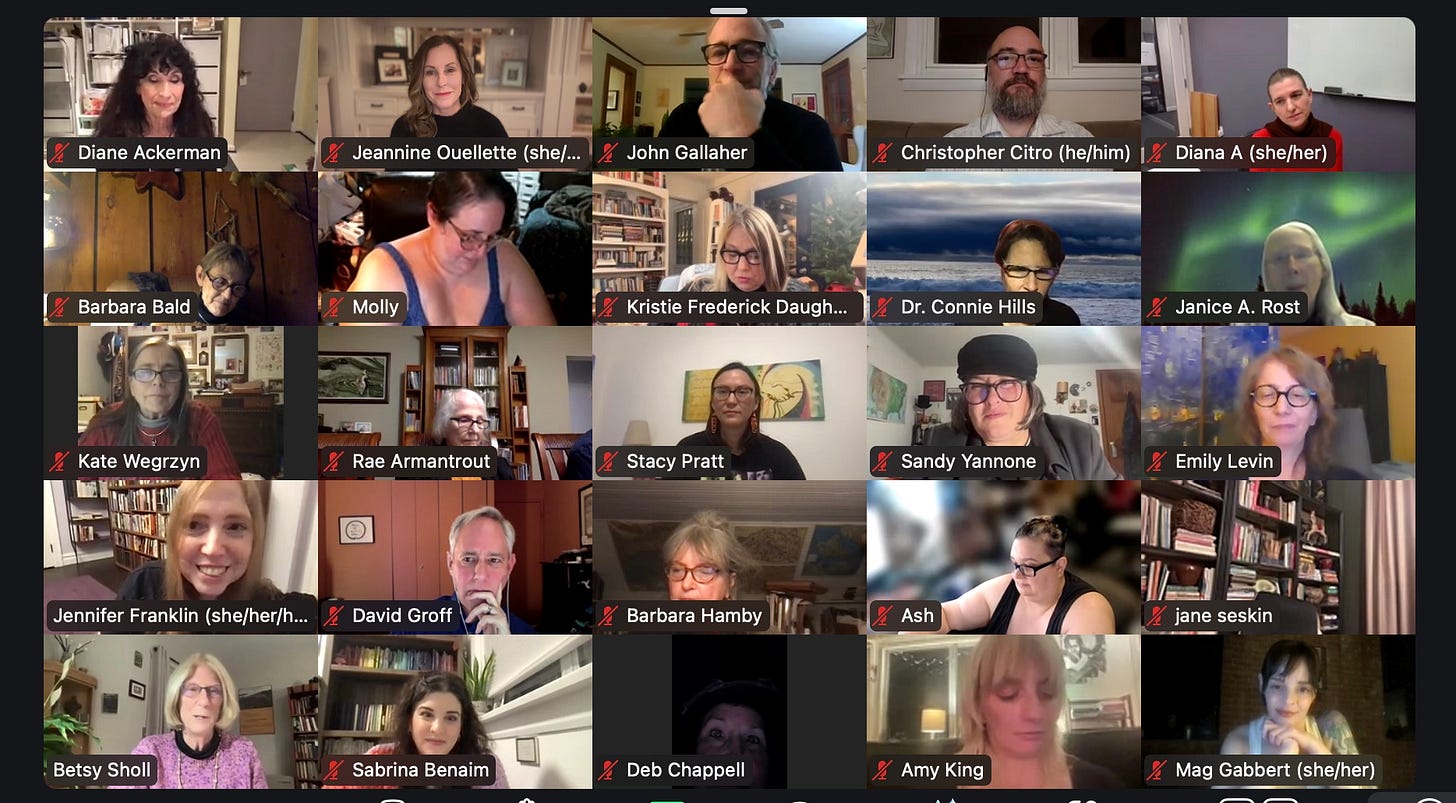

Happy, Happy! Last night’s reading for the launch of Invisible Strings: 113 Poets Respond to the Songs of Taylor Swift, was magical, and it was so joyful to see many WITDers there! Almost three and a half hours of ecstatic poetry from the greatest living poets writing in the English language, with about 250 in attendance at the height of the event.

Incredible.

Z asked

when he saw me on their computer screen, “WHY IS NANA IN THE MEETING?” I am still wondering that myself.And to add to the mystery, I awoke this morning to the LitHub feature highlighting my poem and my outro essay, “Twinkling Is Only An Effect,” alongside the work of Naomi Shihab Nye and Victoria Redel. Dream come true.

You can read the LitHub feature here if you like—and meanwhile, here are some pics of last night’s event below. I’m grateful to my son’s fiance, Kaela, for getting a good pic of me reading, because that’s damn near impossible to do. I make the worst faces—but even then, I’d be happy about last night, an experience I’ll treasure for all my years to come.

Now for slowing time down on the page—this week’s scene topic!

For as long as I have taught writing, I have been teaching writers to tighten their prose, to cut words, lines, sentences, paragraphs, and sections that are not serving the spirit of the work, and to ruthlessly weed their own words. In other words, I have been teaching them, in a sense, to speed up.

What’s funny about this is that I have also, for as long as I have taught writing, been teaching writers to elongate scenes, to let us dwell in the moment long enough to live it, feel it, remember it, and bear its weight. In other words, I have been teaching them to slow down.

This is a perfect example of what I meant last week—in my post refuting the idea that writing instruction steals your voice from you—in which I said, among other things:

What if the writing advice you encounter is often confusing and contradictory, and every time you try to apply someone else’s ideas about about the craft of writing to your own work, you feel less confident instead of more?

Then you’re doing it right.

Creative friction is how we grow.

Creative friction is also how we learn to see how these two contradictory pieces of writing advice can both be true at the same time within the same work, and how we learn to discern for ourselves when to apply one or the other.

This week, we look closely at slowing down, which I’ve always called “elongating the moment.” There are other ways to say it. In her excellent essay on managing time on the page, Rachel Beanland1 tells us that Joan Silber calls it the “slowed scene,” Monika Fludernik calls it “time-extending narration,” Seymour Chatman calls it “the stretch.”

Whatever we call it, the heart of the art is knowing when, where, and how to slow down (or speed up) on the page—and that is an ongoing journey that never ends. As with any journey, it starts with one step, then another.

This week, we’ll look at when to slow time down, and some exact devices and mechanics for doing so. And I will provide three example scenes of slowed time, and my favorite YouTube video2 explaining how to slow time down on the page.

The three examples I have for you come from a Tobias Wolff story, a Great Gatsby scene, and a scene from my memoir The Part That Burns.

We’ll start with my own work, since I know exactly what I did and why I did it. In this scene, the narrator’s mother has just casually acknowledged that she knew, as it was happening, about the years of sexual abuse that the narrator experienced at the hands of her stepfather.

The narrator is trying to take this revelation in:

“You’re saying you knew, when I was little? You knew back then what he was doing, before I told you?” July sun bounces off the smooth surface of North Center Lake and pours brilliant white light into the room. Sophie’s thin baby hair has sprung into sweaty ringlets, and her skin shines pink with summer. But I am shivering. Sophie looks up at me suddenly, her bright round face stretching open like a field toward a distant horizon, much farther away than I can see.

“I’m saying I was worried he might be, might have—and he said, he promised that after that he wouldn’t,” Mom says. “He promised it was over. Still, when he left that time, left Meadowlark Hills, after he smashed the furniture and whatnot, I said he had to get help. I said he had to, or he couldn’t come back.” Her lazy eye goes loose, while her strong eye, aimed dead on me, narrows and hardens. I picture her as a child on the farm in Smithville, with her eye patch and Coke-bottle glasses. I picture her playing in the forbidden woods behind the old tracks, tripping and crashing down on that rusty railroad spike, a perfect arc of blood pulsing from her thigh.

“Mom,” I say. The sound of my own voice is amplified in my ears, as if traveling through deep water. “I was barely older than Sophie.” My throat swells shut around these shards of language.

Mom pushes herself up from the table and carries her coffee cup to the sideboard of that farmhouse sink I love so much. She leans against the porcelain, her broad back to me. From behind, Mom’s hair is both flattened and tufting sideways. It hurts to look at her. I scoop Sophie up and balance her little body around my waist, her plump legs encircling the mound of my pregnant belly. I edge toward the porch door. Mom spins around and claps her hands, once, twice, three times. “Jeannie,” she says. “I am now closing the book on Michael S_______ and this particular sorrow. I recommend you do the same. Every day, women are raped and beaten. They get over it. And so should you. Until then, do not darken my door with your self-pity.”

My mother turns back around to face the sink again, rinses her cup under the faucet, sets it exactly where it was a moment before, then slings her purse over her shoulder. I imagine the silver pin under her skin from the surgery she had after the explosion she survived when she was a new mother; I picture the way the twisted metal keeps her arm stuck to her body as she walks through the narrow hallway, past the steep basement stairs, through the mudroom, and out my back door, her shadow stretching out long before her.

Sophie cranes her neck in my mother’s direction, uncurls her starfish hand to wiggle her fingers slowly at the empty spot where her grandmother just was. “Grandma bye-bye?” she says.

Because this revelation was so pivotal, I wanted to ensure that readers felt its weight. And, as Joan Silber says, in writing, length is weight. I needed to slow down time here.

To do that, I ended up combining four very specific devices that I’m about to highlight, and explain how each performs a specific function in a specific way.