Writing Place as a Map of the Heart

The Power of Place | Week Three | Sometimes, landmarks are more than the sum of their parts

Hello, friends!

Before anything else today, first, my Every Exciting News: I am now represented by the fabulous Laurie Abkemeier of DeFiore Literary.

I could not be more excited!

When I launched Writing in the Dark on Substack 2.5 years ago, I had no social media platform to speak of and a mostly defunct newsletter with a list of 600 current and former students. I didn’t know what I was doing, exactly, but I had recently published my memoir, The Part That Burns, which changed my life, and I was teaching prolifically. I knew I wanted to write about writing.

And now I’m writing a book about it.

I think the moral of the story might be, write toward what you love, and then write it harder. The next day, do that again.

Then again.

Then again.

And so on.

Whatever happens, you will at least have written your way toward love, and that is no small thing.

I hope to continue to write our way toward love together, here, for a long long time to come.

And now, let’s talk about place.

When we talk about grounding our stories in the exterior world—the world we all share and recognize, versus the strange and private dreamscapes of our minds—we are talking, ultimately, about concrete specific details. Things we can see, hear, touch, smell, and taste.

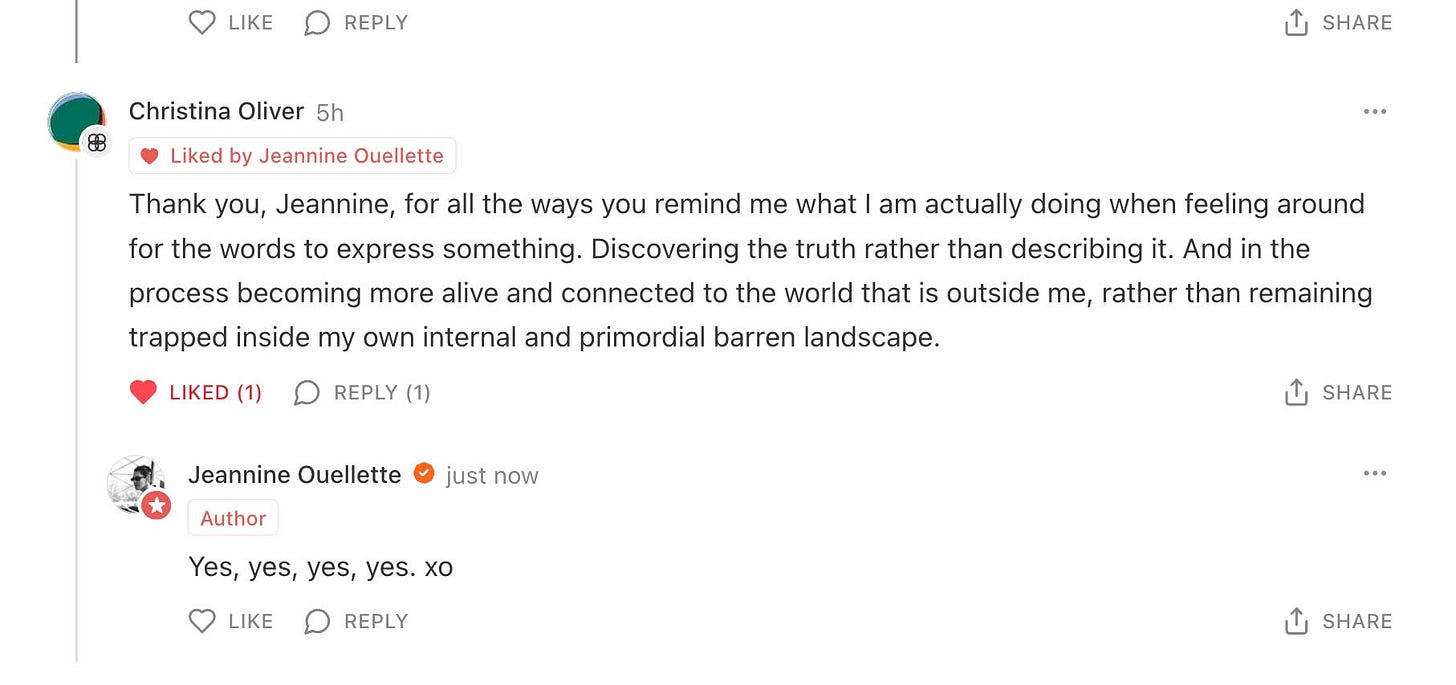

It’s astonishing to me how it is that no matter how many times I think this, say it, teach it, or work my own writing toward it, it continues to feel revolutionary in its power. So, yesterday, when Christina said this under yesterday’s post on writing to become the world, rather than to describe the world, it struck me so hard I actually had to screen shot it and send it to my agent. Why? Because yesterday I gave her the sample chapter for the proposal, which explores attention through multiple lenses, including personal narrative. I said, in the email to my agent (really love using that phrase, haha):

Also: I posted something on Writing in the Dark today that is in conversation with Chapter One, and wanted to share … a comment from a reader that really gets right at the heart of an important--the most important, really--thing I am trying to say in Chapter One.

Exactly, Christina! This is exactly it. Someone else said that they’ve come to realize that internal monologue is like a strong spice: valuable, but to be used sparingly. Yes, that too.

By the time I started writing The Part That Burns in 2015, I was already coming to understand most of what I now teach in terms of the balance of exteriority and interiority, and the astonishing power of attention to detail.

Place, on the other hand, I was not as consciously aware of—that is to say, I wasn’t necessarily thinking overtly about place. I was thinking about the story that had lived inside of me since childhood. The story that, as Cheryl Strayed said about her first book, was beating inside my chest like a second heart. I was thinking about the urgency I felt to give voice to that story so that it could live outside of me, separate from me, as a work of art, which in turn would change the way it rested against my ribs.

And it did.

But, although I was not thinking overtly about place, I was surely mired in it by organic necessity. I even featured it prominently in the jacket copy, which, because I published with a small indie press, I was allowed to write myself:

Jeannine Ouellette recollects fragments of her life and arranges them elliptically to witness each piece as torn and whole, as something more than itself. Caught between the dramatic landscapes of Lake Superior and Casper Mountain, between her stepfather’s groping and her mother’s erratic behavior, Ouellette lives for the day she can become a mother herself and create her own sheltering family. But she cannot know how the visceral reality of both birth and babies will pull her back into the body she long ago abandoned, revealing new layers of pain and desire, and forcing her to choose between her idealistic vision of perfect marriage and motherhood, and the birthright of her own awakening flesh, unruly and alive. The Part That Burns is a story about the tenacity of family roots, the formidable undertow of trauma, and the rebellious and persistent yearning of human beings for love from each other.

Those dramatic landscapes pressed themselves into the pages of my book all on their own:

It must be fall. It’s not winter. In Duluth, if you open the door to winter, you know it. Lake Superior is the reason. This lake is too big, too deep. And our city is high north, almost as high as north gets. We are carved into the rocks. The cold never leaves here—not all the way.

We don’t live in Duluth anymore. The house on Twenty-Fourth Avenue where Rachael was born was our last house before Wyoming. Wyoming has mountains and cactuses and barbed wire but almost no lakes or trees.

Brandy and Pete run free behind our house. Back there, you have emptiness all the way to Casper Mountain—it’s just greasewood and short grass, plus millions of sagebrushes. Old sagebrushes are hard and twisted but baby ones have nice soft hairs. Mama says Wyoming is ugly, but I think she’s not looking with her eyes. Some cactuses have tiny flowers. If you stand still, you might see a lizard or some bright yellow birds. You might even see a jackalope. But probably not, because jackalopes aren’t real. My favorite thing behind our house is the smell—dark and peppery with something sweet I don’t know.

Mama brings us on one of her long drives, like she does. We go all the way past the edge of the city. “Country roads,” Mama says. She drives and drives and we get a little lost but Mama doesn’t seem to mind. She looks pretty with her hair pulled back under a blue bandana. On the radio is “Hey, Jude.” Finally, Mama parks under some low trees with branches growing straight out instead of up. Next to the trees, a small creek. “Worthless trickle,” Mama says. She misses the creeks in Duluth. Rachael stomps in the trickle while Mama and I sit under the tree. Mama smokes her True Blues. “I should learn to paint,” Mama says. Smoke slips out of her nose in soft white puffs. “Not everyone has a gift. But I might.” She flicks her ash. “How about we girls keep driving? Like gypsies. Like thieves in the night.” Mama’s lazy eye is doing that thing. She had a patch when she was little, but it didn’t work all the way.

Although shabby, our new house had the best bones of any on the block. It was very good stock for Northeast, a working-class neighborhood settled mostly by Eastern European immigrants and known for having both a church and a bar on every corner. Northeast streets are named for U.S. presidents in the order in which they held office. “Andrew Jackson was the seventh president of the United States,” John told me. “Dirt poor and orphaned during the Revolutionary War, a kid with no education from a backwater cabin in the Carolinas, and he makes it to the Oval Office. How do you like them apples?” John was twenty-five now, and a social studies teacher. He knew things. He also knew this neighborhood, having grown up a few blocks away on Madison Street. The school where he taught was nearby as well. John liked things to stay the same.

These are just a few of the many, many passages in The Part That Burns that feel, to me, grounded in place.

And within these passages and others, there are landmarks that mean something to the narrator—like these (and more):

The green house on the steepest hill

The corner store at the end of the block on Duluth’s 24th Avenue

Lake Superior

Casper Mountain

The empty fields behind the house on Meadowlark Lane

The fresh asphalt streets of that new subdivision

North Center Lake in Center City

The isthmus connected to Center City

Wide open country roads

The list goes on. These places, I think, take a stand in my memoir—they press themselves into the pages with enough obstinance and force to feel, I dearly hope, imbued with enough life to in turn exert force on the narrator.

And that—place exerting force on the narrator/character—is what we want, and what we saw so beautifully wrought last week in Margaret Atwood’s beautiful passages.

Place, we’re seeing as we journey through this intensive, is not setting. It is active. It does so much more than provide a backdrop. Among other things, place:

Roots Characters: Sense of place gives characters a home, work setting, and a backdrop for their challenges.

Enhances Realism: It creates a transporting feeling for the reader, making the book's world feel as real as their own.

Aids Suspense of Disbelief: A well-developed sense of place helps readers accept the story's world, even if it's fictional.

Shapes Narrative: The constraints and details of a setting can exert significant force on the plot and events of a story.

For many of us as human beings, the place that exerts the most force on who we become is our childhood home/neighborhood. Its streets and houses or buildings, its traffic sounds or lack of, birdsong or lack of, children’s voices or lack of. Its stores and churches or temples or mosques. Its bars. Its schools and parks and playgrounds and friends’ homes and abandoned lots and condemned houses and secret passages and gulleys and creeks and hills and old trees and water towers and skating rinks, etc. etc. etc.

These landmarks are, especially when we are children, more than places. The take on emotional meaning and exert that “significant force” we’re coming to understand about place. Later, of course, these landmarks live in our psyches and in our bodies (I can still feel in my body the way it felt to penny drop from the monkey bars at Hall Elementary School).

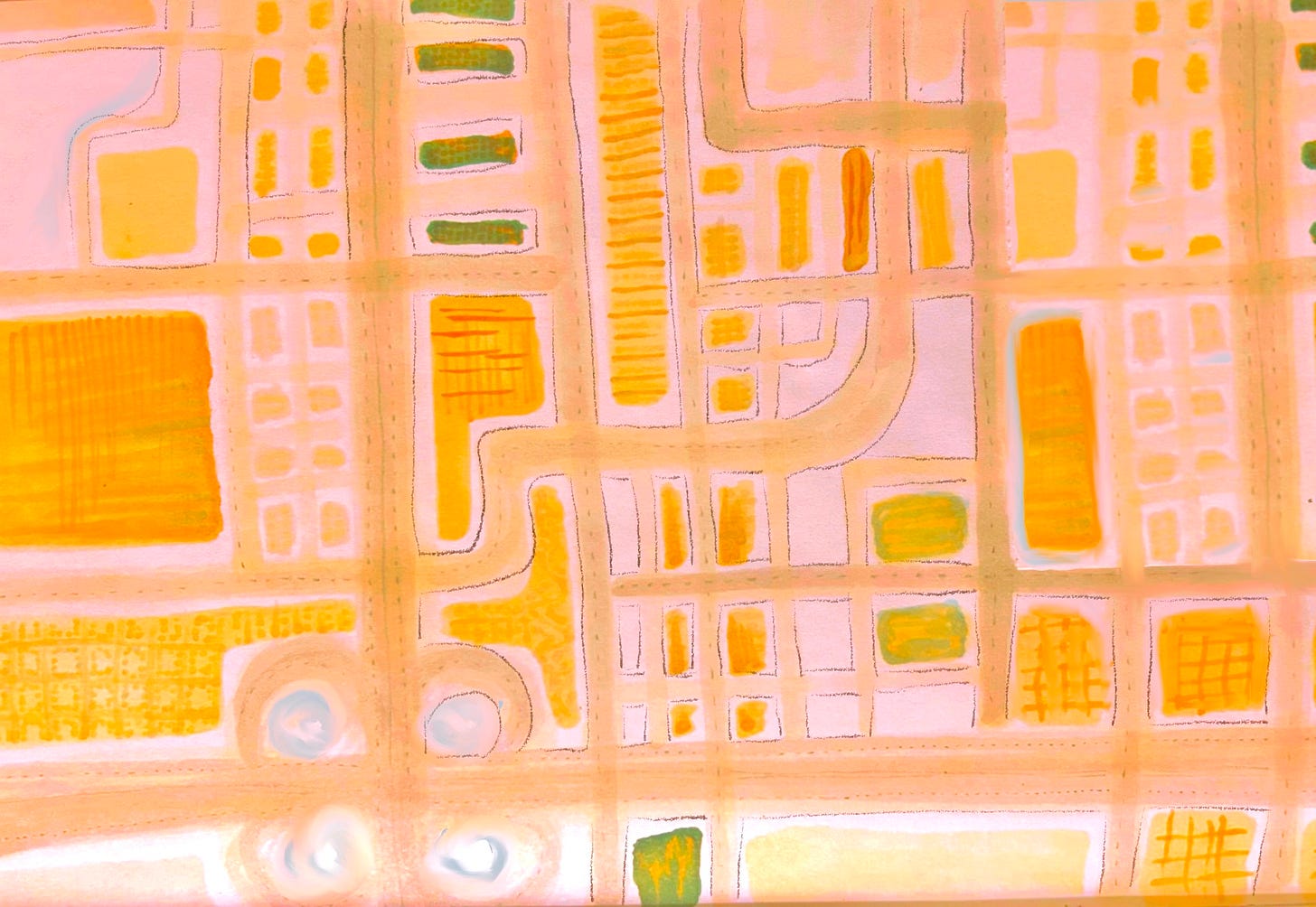

So, this week we’ll return to our childhood neighborhoods and see what we can recreate and conjure there.

This three-part exercise should help us get there!