All the Shit You Don't Want

“There is no such thing as pure pleasure; some anxiety always goes with it.” ~Ovid

In Janet Burroway’s iconic textbook Writing Fiction, she says something along the lines of how plot = trouble, which she elaborates upon by explaining that a picnic wherein the sun shines, the grass is soft, the sandwiches are tasty, and the lover is fine, is … boring. On the page, we need a good thunderstorm, a swarm of insects, and a big fight to keep things moving.

That’s not what today’s headline refers to, but

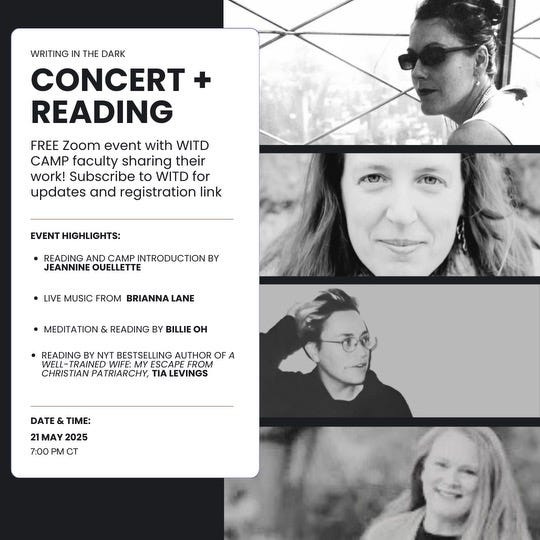

’s drawing reminded me of it, and it’s not totally irrelevant to what we might see when we look super closely at Mary Oliver’s “The Summer Day” through the lens of pleasure and pain.First, though, a quick last reminder of tonight’s free READING + CONCERT in celebration of our upcoming Writing in the Dark | The CAMP. This event is free to all, and all are welcome! Music by CAMP faculty musician, Brianna Lane (have a listen, here!) and readings by CAMP featured writer Tia Levings, NYT bestselling author of A Well-Trained Wife, plus Billie Oh, and me. Zoom link below! Please join us!

And now, back to the topic at hand: pleasure and pain.

Last week, I read a fascinating post by

on what she called a “subversive gratitude practice,” which she says she learned from a lesser known book by Melody Beattie (author of the famous Codependent No More), who, Whitaker said, died last February with little media fanfare—a seemingly rare example of an accomplished writer of 18 books who opted out of social media.The name of the lesser-known book? Making Miracles in Forty Days—a title that Beattie hated, according to Whitaker’s essay, which quotes yet another interview with Beattie.

Anyway, what Whitaker said about Beattie’s subversive gratitude practice—in her otherwise intricate and absorbing essay about Beattie1—an essay that all writers should read, because it’s such an honest depiction of what the '“successful writing life” can look like closer up—was, among other things:

… but her book on a subversive gratitude practice that I wrote about here and that Ann Dowsett Johnston also wrote about. This is an important fact because Ann and I are friends with a similar kind of edge to us, we found this obscure book separately, and I think it was only someone as complicated as Beattie who could have gotten either of us into practicing a proper kind of gratitude that includes being grateful for all the shit you don’t want. I think I mean, it was only someone who so clearly knew the dark that I trusted to lead me to the light. I think Ann would say the same.

So why are we talking today about a subversive gratitude practice that involves being grateful for “all the shit you don’t want” rather than just the shiny or simple blessings we can otherwise so easily count?

Because pleasure requires that we open ourselves to the inevitability of pain and loss. Oh, have I mentioned this is our final week of the Writing Toward Pleasure intensive?! Well, it is. So we might as well go for gold and get as complicated as we can.

For this reason, I’m thinking still about the complexity of pleasure—and, really, the complexity of all good things—and how that complexity is inevitable, perhaps due to the duality of all things, the yin-yang nature of life. As Ovid said, “There is no such thing as pure pleasure; some anxiety always goes with it.”

I wonder, is the anxiety rooted in our anticipatory sadness over pleasure’s end? Knowing, as we do, that nothing lasts? Or is the anxiety rooted in our fear of relaxing fully into pleasure, for fear we will lose ourselves in it entirely, to the point where we never return to the here and now of life, the here and now of described so beautifully in Marie Howe’s incredible poem, “What the Living Do,” 2which we looked closely at in Writing in the Dark | The SCHOOL last week:

This is the everyday we spoke of.

It’s winter again: the sky’s a deep, headstrong blue, and the sunlight pours throughthe open living-room windows because the heat’s on too high in here and I can’t turn it off.

For weeks now, driving, or dropping a bag of groceries in the street, the bag breaking,I’ve been thinking: This is what the living do.

Maybe the anxiety, if it’s true that pleasure always contains a drop of it, is rooted in both anticipatory sadness over pleasure’s loss and fear of being subsumed by it?

In any case, these were my thoughts as I cobbled together today’s deep dive into the pleasure waters in which we’ve been swimming (a sentence that brings be right back to our Elizabeth Bishop conversation last week). Thoughts, that is, about what it really means to experience pleasure in a human body, and how we can notice more of it. For it may be, in the end, the noticing that is itself the pleasure (Marie Howe’s “What the Living Do” certainly points in that direction).

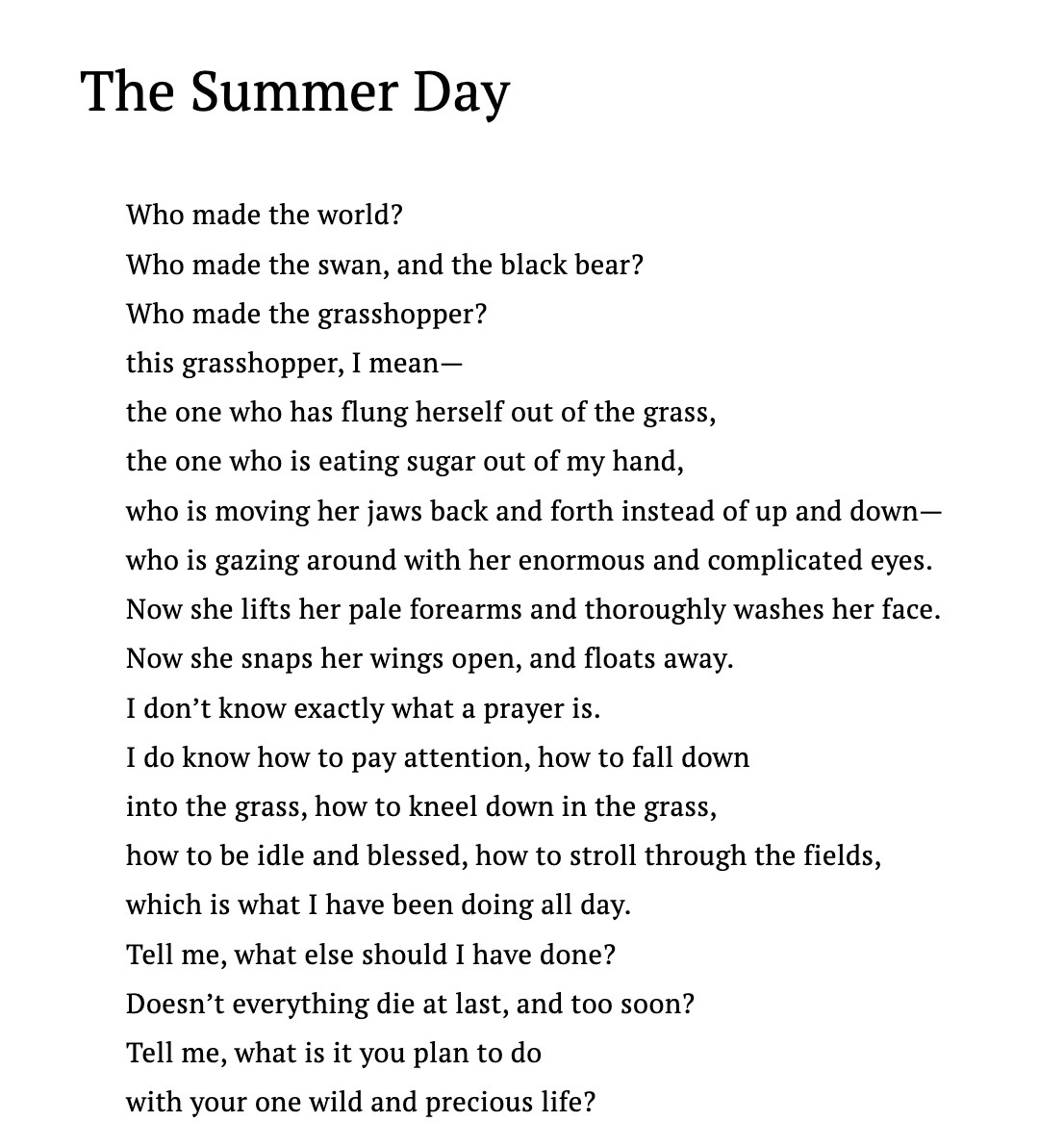

So, while I’ve taught Mary Oliver’s poem “The Summer Day” many times before—all the way back to the early 2000s in fact, when I taught it to sixth-graders, including Krista Tippett’s daughter Aly, who ended up reciting it for Mary Oliver, which I’ve written about and which you can listen to here—I’ve never taught it through the lens of pleasure.

Let’s see what happens when we view this well-worn work through pleasure’s closest lens, and write in response to it, from that precise perspective.

Normally when I teach “The Summer Day,” my emphasis is on attention, and the rich, concrete sensory detail of the poem, how it results in an immersive, textured, and embodied experience for readers. It’s a poem that brings us into the immediacy of being alive.

There’s a story about this poem—one I think I heard from Mary Oliver herself at a reading years and years ago in Minneapolis. As that story goes, Mary Oliver was at a birthday party when this poem began, a party at which a grasshopper really did hop into her hand and begin eating the crumbs and frosting from the birthday cake. That moment, closely observed, led to her unforgettable description of the grasshopper, a description that struck me on first reading and has never left my mind since, truly, for whenever I see a grasshopper or even think the word “grasshopper,” I hear these lines:

the one … who is moving her jaws back and forth instead of up and down—

who is gazing around with her enormous and complicated eyes.

Now she lifts her pale forearms and thoroughly washes her fasce.

Now she snaps her wings open, and floats away.

It is the most precise, strangest, captivating description of a grasshopper I can possibly imagine. It is entrancing.

What’s also notable about this poem—there is so much to note—is how Oliver begins with her series of questions:

Who made the world?

Who made the swan and the black bear?

Who made the grasshopper?

this grasshopper, I mean—

the one who has flung herself out of the grass,

the one who is eating sugar out of my hand …

It’s interesting to see clearly how Oliver begins expansively, with “the world,” then moves us in a little closer with the swan and the black bear, then closer yet, with something smaller—the grasshopper—then closer yet, with “this grasshopper, the one … who is eating sugar out of my hand.”

And just like that, we are right there in the palm of the poet’s hand, looking into a grasshopper’s “enormous and complicated eyes.”

See how she did that?!

It’s extraordinary, truly.

And after the grasshopper snaps her wings open and floats away (notice the beauty of those verbs, “snap” and “float”), Oliver pivots hard, and announces (emphasis mine, to show the turn):

I don’t know exactly what a prayer is.

I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down

into the grass, how to kneel down in the grass,

how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields,

which is what I have been doing all day.

Tell me, what else should I have done?

This is a sensuous kind of pleasure that Oliver describes. Not erotic, per se, but deeply embodied. The speaker’s attention is tactile and spiritual at once. We can feel the grass, the warmth of the day, the hush of presence.

Can we also feel, though, the the slight tension in the question “Tell me, what else should I have done?”

We know, or at least can strongly sense, that the speaker of this poem is celebrating her choice to be “idle and blessed,” to “stroll through the fields.”

But we also know that we cannot, in fact, be idle and blessed all day every day. Or, at least, most of us have not figured out a way. The best we can do is hold on, best we can, to the truth that idle and blessed—falling down into the grass, kneeling down in the grass—is a state that is available to us, a state we neglect at our own peril, as suggested by the poem’s final and most iconic line of all:

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

With your one wild and precious life?

Now let’s write ourselves. And why not? What else should we do?

Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon?

Yes, it does. But even still, I have never seen a group of people write in response to “The Summer Day” and not come up with something, even if just a line or two, that they love.

Let’s see.